Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

forward and step back in a frustrating but sustainable

manner, or one can attempt to storm the slope, running fast

enough compared with avalanche speed, that one can more

efficiently ascend. The choice here is a matter of decorum,

fitness, luggage and time of day; unencumbered young

students on a brisk morning seeing a brief opportunity to

experience dunes may enthusiastically embrace the latter

approach, a senior researcher making a long traverse with a

heavy GPR (see

Chap. 11

) on a hot afternoon may have to

plod on with the former.

Of course, people are not the only entities that walk on

sand. Everything from elephants (in Namibia) to beetles do

so. Some species have particular adaptations to desert sur-

vival and migration, most notably the 'ship of the desert',

the camel (Fig.

22.2

). Its long legs keep the body elevated

above the hot sand and give the stride needed for long

traverses. The famous hump is filled with fatty tissue (which

acts as a water store—fats contain more water per calorie

than do other tissue energy stores). These are general arid-

lands adaptations; specific to sand, however, are the fact

that the camel's wide feet splay out to minimize the ground

loading, and camels have long eyelashes and can close their

nostrils to cope with blowing sand and dust.

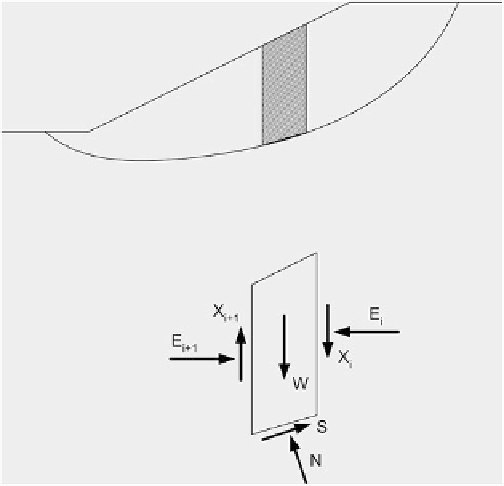

Fig. 22.1

A schematic of how the failure criterion of a sloping soil

such as a dune face can be computed by the so-called 'method of slices'.

The soil is assumed to fail along a curve surface: the forces on each slice

are estimated given the loading by the soil's weight and any exterior

loads. When the required frictional force S can no longer be provided by

the soil, the material will fail. Image US Army Corps of Engineers

Fig. 22.2

Camels are suited to

desert travel not only because of

their humps, but also because of

their wide feet which reduce

ground loading. First author, in

Egypt

Search WWH ::

Custom Search