Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

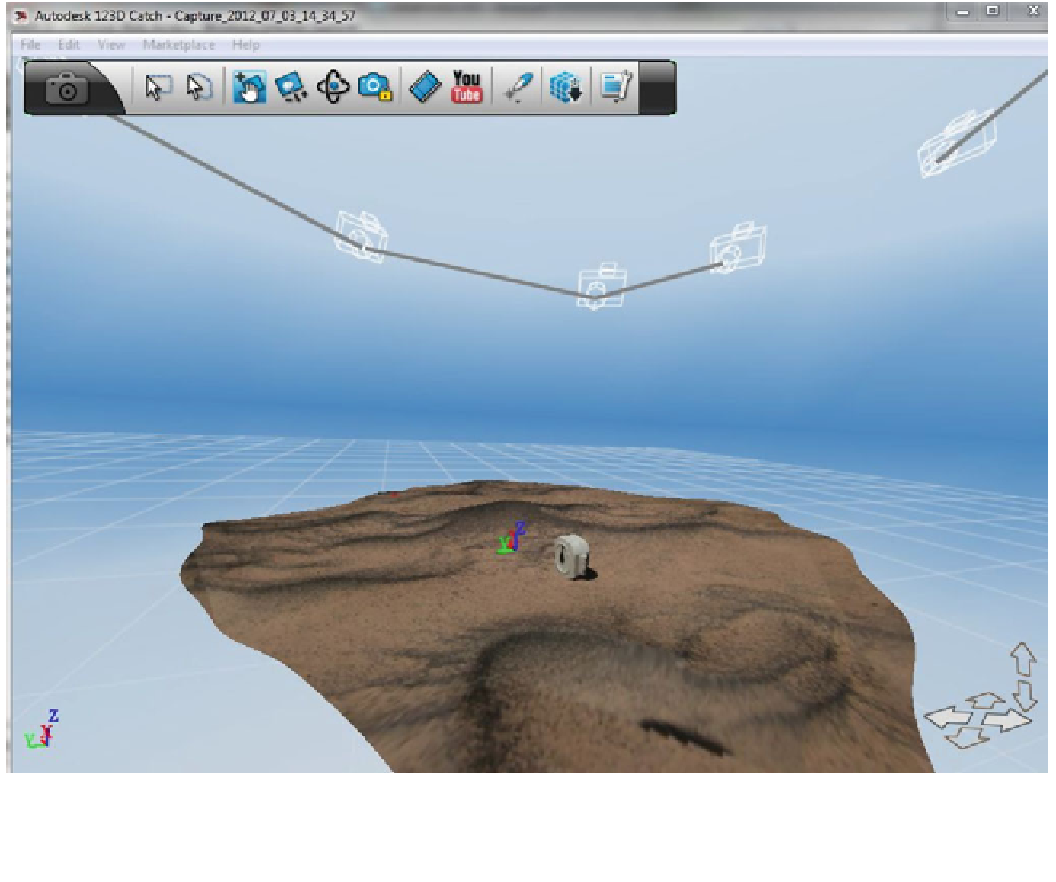

Fig. 16.4

Screenshot of an auto-photogrammetry program (Au-

todesk's 123DCatch) showing the image texture draped over a digital

model of the shape of some ripples; the model can be spun around to

be viewed in different directions, or exported for numerical analysis.

The positions of the camera that have taken the images are

automatically estimated and are shown at the top. A Brunton compass,

in homage to earlier methods, is used to show the scale of the ripple.

Photos J. Zimbelman

used to document changes in dune shape, or in the position

of ripples. So far, no movies of dunes in motion have been

made, but it is likely just a matter of time.

Ripple migration has been observed with timelapse

imaging in Egypt by Lorenz (2011) and at Great Sand Dunes

National Park and Preserve, e.g., Fig.

16.5

, by Lorenz and

Valdez (2011). These papers describe some image process-

ing techniques that can help sift through the prodigious

amount of data that movie sequences can generate. These

observations were used to estimate ripple migration rates

shown in

Chap. 9

from about 1 to 15 mm/min. Sullivan et al.

(2008) report measuring the migration of ripple crests on

Mars by 2 cm towards the Spirit rover at Gusev crater

between sols 1260 and 1265 during a particularly windy

period in 2007 (the first time movement of whole bedforms

was documented by a surface vehicle—see Fig.

16.15

).

Finally, although this verges on aerial photography (see

Chap. 18

), it is possible—indeed, now rather easy, given the

availability of very small digital cameras with timelapse or

video settings— for scientists in the field to obtain images

from a vantage point tens or hundreds of meters up by using

remote-controlled planes or helicopters. These are rather

fun to use, and make a useful bridging scale between the

1-2 m height of field photographs and the distant per-

spective of true aerial or orbital imaging. Aber et al. (2010)

discuss at length the possibilities and techniques of

small-scale aerial photography from kites, drones and bal-

loons. An exciting possibility is the combination of kite

imaging with the new photogrammetry tools mentioned

above to build shape models of dunes quickly in the field.

16.2.3

Thermal Imaging

We discuss thermal imaging in more detail in

Chap. 18

, but

note here an effect seen in field imaging with hand-held

thermal cameras. Avalanching flows can bring sand to the

Search WWH ::

Custom Search