Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

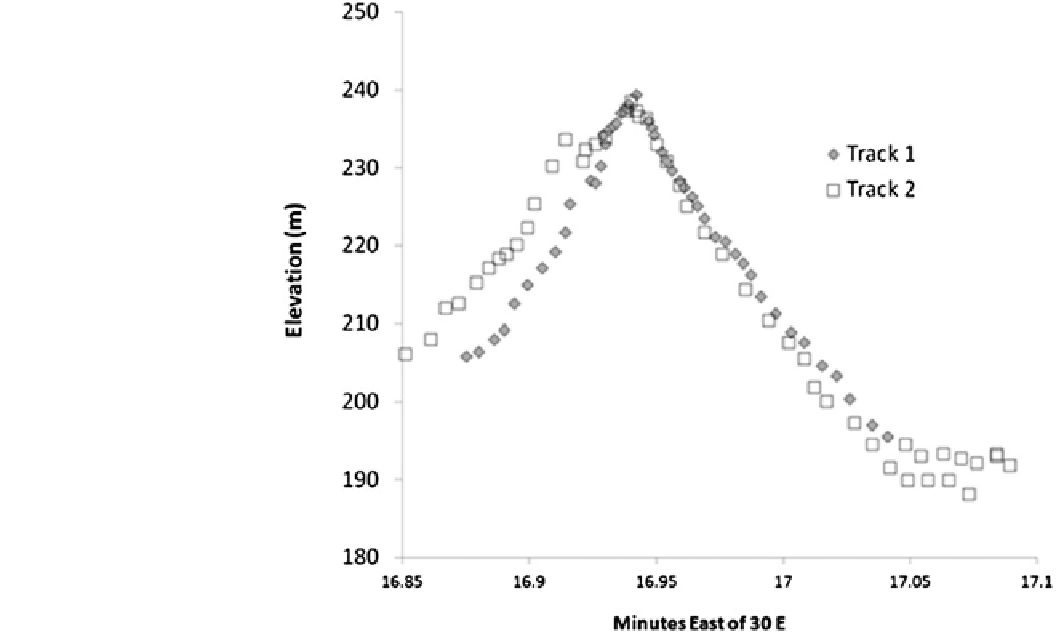

Fig. 16.2

Two adjacent GPS

traverses across a linear dune in

Quattaniya, Egypt (see also

a simple handheld GPS receiver.

The traverse is about 300 m long;

the dune grades into a wide

shallow plinth, not shown here, to

the west (left) and is about 50 m

high

user depends on the distance between the receiver and each

satellite, so each time measurement defines a spherical shell

in space where the receiver must lie. Having fixes from

several satellites defines several shells, and the intersection

of these shells defines a small volume (usually only a few

meters across) in which the receiver must lie. All this

elaborate calculation was performed by computer in back-

pack-sized units in the 1980s, which progressively shrank

(more or less in parallel with the comparable technology in

mobile telephones) to handheld units in the 1990 and 2000,

and

migration, it is generally the case that the relative positions

of the slipface, crest, etc. are more important than the

absolute position in some reference frame). Convenient

tools now exist (notably Google Earth) to overlay GPS

tracks on satellite imaging (see Fig.

9.5

).

For higher precision (centimeters) a technique called

differential GPS must still be used (it had already become

popular to circumvent the limitations of the SA policy),

wherein a fixed base station and a mobile survey unit

simultaneously record fixes. Since many of the errors (such

as those induced by the propagation of the signal through

the ionosphere) are common to both receivers, they cancel

out when the position of the survey unit relative to the base

station is calculated. Because the accuracy is so high, the

antenna of the survey unit is often mounted on a staff so that

its distance from the ground can be precisely controlled as

the surveyor walks around; a backpack (Fig.

16.3

) is a more

convenient and often adequately accurate solution.

then

mere

thumbnail-sized

devices

incorporated

in

phones and other appliances in the 2010s.

In the 1990 and 2000s, when GPS units became available

and affordable for scientific use, the out-of-the-box accu-

racy was often poorer than some tens of meters, since the

'native' precision of the signals was restricted to US mili-

tary users, a policy termed 'Selective Availability'. How-

ever, in 2000, the SA policy was revoked, allowing

accuracies of a few meters to be obtained with only a single

handheld receiver. This has made mapping the boundaries

of geological features like dunes, or measuring their profiles

by marching or driving across them, almost trivial.

Rather effective shape models of dunes even only a few

meters high can now be constructed with simple handheld

GPS units (which can be set to record coordinates at short

intervals, and can then be downloaded to a computer— e.g.,

Fig.

16.2

.). The accuracy of these may vary, but can be just

a few meters (and except for the measurement of dune

16.2.2

Imaging

Dunes are naturally photogenic targets. G.K. Gilbert's

photographs from the 1890s (a number of which appear in

this topic) are striking were largely enabled by the inno-

vation of photographic film, which let the geologist take his

own pictures (rather than needing a dedicated photographer

along, as had been the case only a decade or two before

Search WWH ::

Custom Search