Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

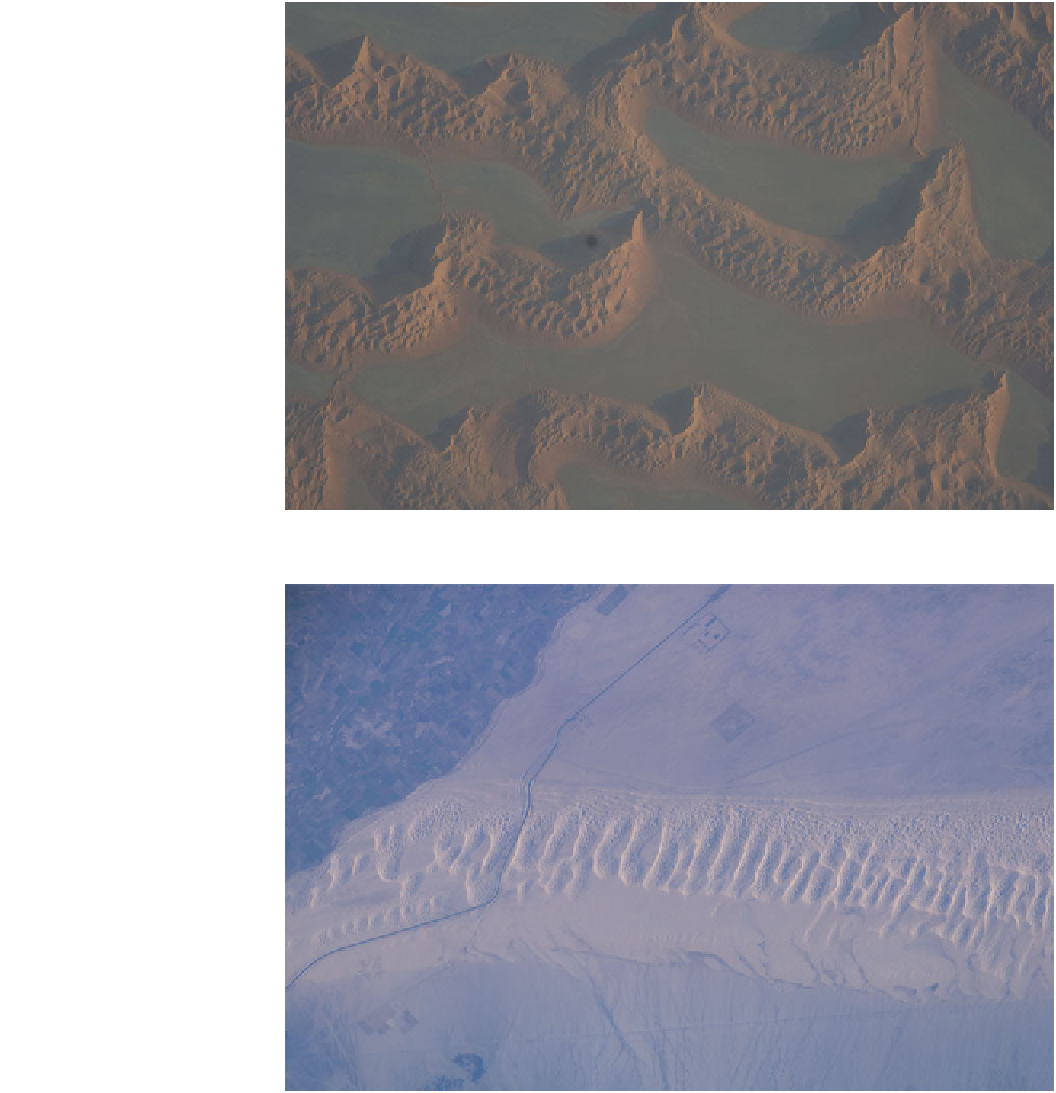

Fig. 7.16

Megabarchans in the

Rub' Al Khali desert, seen from

the International Space Station

(south is up). These dunes have a

spacing of about 2 km, with

*100 m superposed barchanoid

forms. Credit NASA JSC EOL

Fig. 7.17

Complex dunes of the

Algodones in southern

California, seen from the

International Space Station. For a

view of the same dunefield from

an airliner, see Fig.

24.6

; for a

radar view of these dunes, see

Fig.

18.18

. West is up. Irrigated

fields in Mexico are at left, just

beyond the 'sand dragon' border

American canal, and Interstate-10

cut across the dunefield, which

grades from some narrow linears

and small barchanoids at the top,

to massive (*1 km-spaced)

compound ridges, and a sand

sheet at the bottom. Credit

NASA/JSC/EOL

of the dune itself. Some examples on Namib linears can be

seen in Fig.

18.24

. A field example with small incipient

transverse ridges is shown in Fig.

7.13

.

Dong et al. (2010) recognize this form with subsidiary

ridges perpendicular to the main linear dunes in the Kum-

tagh desert in China as 'raked' linear dunes. It may be that

these are the result of a change in wind regime—dunes built

up as linears in a bidirectional regime and winds from one

of those directions have since diminished, resulting in the

accumulated sand now blowing in a more unidirectional

fashion (e.g., Fig.

7.14

). This leads to barchan-like slip

faces periodically along the former crest; a similar effect is

seen in water tank experiments by Reffet et al. (2010). An

alternative idea is that ridges may grow as an 'orthogonal

mode', creeping upwind in the manner that the arms of star

dunes grow. More work is needed—likely exploiting

these evolutionary mechanisms.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search