Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

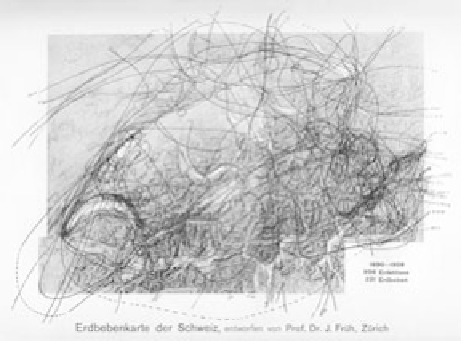

fig. 4.1. Earthquake map of Switzerland, based on the first thirty years of the

Earthquake Commission's activities, during which it collected seven thousand

felt reports. Johannes früh, “ueber die 30-jährige Tätigkeit der Schweizerischen

Erdbebenkommission,” in

94. Jahresversammlung der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden

Gesellschaft,

vol. 1,

Vorträge und Sitzungsprotokolle

(1911).

Geologists today view earthquakes on Swiss territory as the continuing

effect of the collision between the European and African plates that began

the formation of the Alps approximately 80-90 million years ago. Strong

earthquakes occur infrequently, but small tremors are common and often

accompanied by distinctive sounds. In the Alps, earthquakes can trigger

rock slides or avalanches or make rivers impassable. Today earthquakes are

estimated to represent one-third of Switzerland's total disaster risk.

5

According to the calculations of the Swiss Earthquake Commission, be-

tween 1880 and 1904 there was an average of six to seven “Swiss” earth-

quakes per year—meaning seismic events separated in time, observed by

at least two people, and with epicenters inside the Swiss borders.

6

(See fig-

ure 4.1.) Before the commission began its work, earthquakes in Switzerland

were often not recognized as such. Many residents mistook them for strong

winds or thunder. It was not uncommon for people to accuse their upstairs

neighbors of making noise that was actually seismic in origin. In some cases

witnesses were aware only that the horse pulling their carriage had stopped

dead in its tracks.

7

Some residents attributed the vibrations to an “invasion

of a legion of cats, mice, or rats in the garrets.”

8

These tremors rarely caused

much damage: “In general buildings have very infrequently been damaged,

thanks to their solid construction, in particular of the wooden buildings of

the mountain region. In many cases cracks in walls and in the ground, ava-