Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

In the late 1980s and 1990s, global oil supply began to in-

crease when better extraction techniques were developed and

new reserves, such as those in Alaska's North Slope and in the

North Sea of Europe, were systematically tapped. As a result,

prices fell dramatically to about $15 per barrel and Americans

generally moved away from fuel-efficient cars to sport utility ve-

hicles (SUVs), which consumed far more fuel. At the same time,

suburban development in the United States exploded in associa-

tion with urban sprawl (see Discover—

Urban Sprawl

above) and

the length of daily work commutes increased. Global oil prices

slowly began to rise again in 2004 and reached about $88 per

barrel in 2006, in large part because of rising demand in China

and India, which have rapidly growing populations. Prices rose

quickly in late 2007 and early 2008 when future supply fears,

speculation, and a weak dollar pushed the price of a barrel of oil

to over $140. This rapid increase caused prices at the pump to ex-

ceed $4 per gallon in many places within the United States. Just

as consumers were adjusting to this new reality, the world expe-

rienced a massive financial crisis in late 2008 and supply fears

decreased due to a deepening global recession. At that time, the

average price for a gallon of gas in the U.S. midwest was about

$2.70. Since then, the economy has gradually expanded and the

demand for petroleum thus increased. As a result, the average

price for a gallon of gas was about $3.40 in October, 2013.

At the time of the most recent economic downturn,

concerns abounded that global oil supplies were reaching a

critical level that could dampen economic growth for the fore-

seeable future. The U.S. economy has long been vulnerable to

tight supplies because we consume about 25% of the world's

oil (even though we have only 4% of the population) to keep

our industrial society humming. Given our own low supplies

of easily accessible oil, we now import about 60% of what

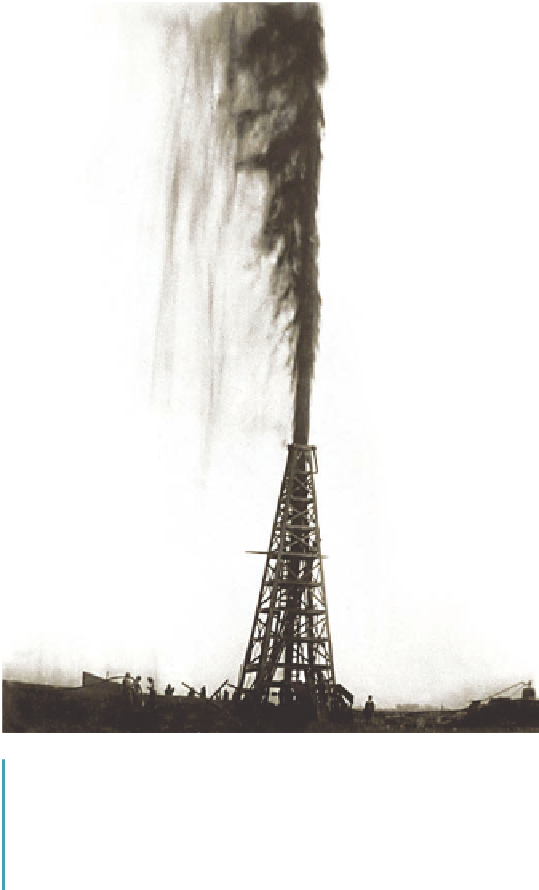

Figure 20.23 The Lucas gusher.

In 1901 the Corsican oil field

in southeastern Texas was tapped by Patillo Higgins, a self-

taught geologist. The pressure in the well was so great that the

oil (or “black gold”) erupted to a height of about 50 m (150 ft) for

9 days after the initial strike. Approximately 1,000,000 barrels of

oil were lost, which would be worth about $17,000,000 today.

approximately 4 billion barrels per year. At about this same

time, oil companies such as Shell and British Petroleum dis-

covered huge reserves in the Middle East and Venezuela that

dwarfed our own. These reserves were ultimately nationalized

by the host nations, which then formed the

Organization of

the Petroleum Exporting Countries

(OPEC) to coordinate pe-

troleum policies.

The economic geography of petroleum began to change

in the late 1960s as the United States slowly reached peak oil

production, which occurred in 1971. Our demand had grown

to the point where we had to import another 23% from for-

eign sources to meet our needs. Our vulnerable dependence

on foreign supplies first became apparent in 1973 when

OPEC organized an oil embargo to flex political muscle.

As a result of this disruption in supply, prices in the United

States jumped and long gas lines were commonplace (Figure

20.24). In an effort to conserve gasoline, the speed limit on

the nation's highways was lowered to 55 mph, and automo-

bile manufacturers focused on building fuel-efficient cars.

Yet another embargo occurred in 1979, further disrupting

supplies and increasing gas prices. Throughout most of the

1980s, global oil supplies were tight and prices at the pump

remained high.

Figure 20.24 Gas lines in the early 1970s.

Waiting for gasoline

like this was a common occurrence during the first oil embargo

because service stations often ran out of gas.