Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

late Tom Schopf, told Sepkoski that he was up for tenure considera-

tion that year. Such an announcement, like the discovery that one is

to be hanged in a fortnight, "concentrates [the] mind wonderfully."

3

In a "panic to publish quickly, the young professor decided that his

best bet was to try to get out an article based on his compendium.

Sepkoski worked frantically for months, only to have Schopf return

to say that he had been mistaken—Sepkoski's tenure would be

decided the

following

year. But by this time Sepkoski had gone too far

to turn back.

Raup had the idea that instead of merely perusing the compen-

dium (a task sufficiently boring as to cause even a quantitatively

minded paleontologist to nod off) it might be examined with the

aid of a computer to see whether any interesting patterns emerged.

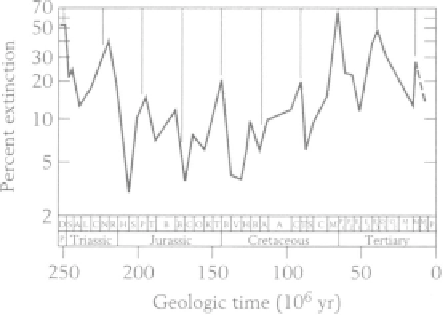

Raup and Sepkoski viewed an assortment of graphical computer

plots, even standing across the room to see whether a pattern recog-

nizable only as a "gestalt" would emerge. Sepkoski suggested that it

might be interesting to compute how the rate of extinction had var-

ied through time. A few days later, Raup brought the new plot,

shown in Figure 25, into Sepkoski's office. "Do you see it?" he asked,

"They're regularly spaced in time."

4

Raup had culled Sepkoski's data in the following ways: He had

examined only the most recent 250 million years, when geologic ages

are more precisely known; he had removed families whose ranges or

identity were poorly known; and, since we have no way of knowing

how long they may live, he deleted families that have not yet become

extinct. He divided the 250 million years up into the 39 stratigraphic

stages that geologists have recognized (geologists divide time into

eons, eras, and periods; rock units into systems, series, and stages—the

FIGURE 2 5

Raup and

Sepkoski's 1984 plot of

extinction periodicity.

5

The

best-fit cycle, at 26 million

years, is shown by vertical

lines.