Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

the load, the current fl owing through the stressed rock increased very rapidly, similar

to what we had observed during the experiment shown in Figure 2b. In addition, the

current fl owing through the rock in the unstressed portion also increased signifi cantly.

Even when we widened the distance between spot 1 and 2, the effect remained, indi-

cating that spot 1 and spot 2 were “talking to each other electrically” beyond the range

over which the mechanical stress was transmitted.

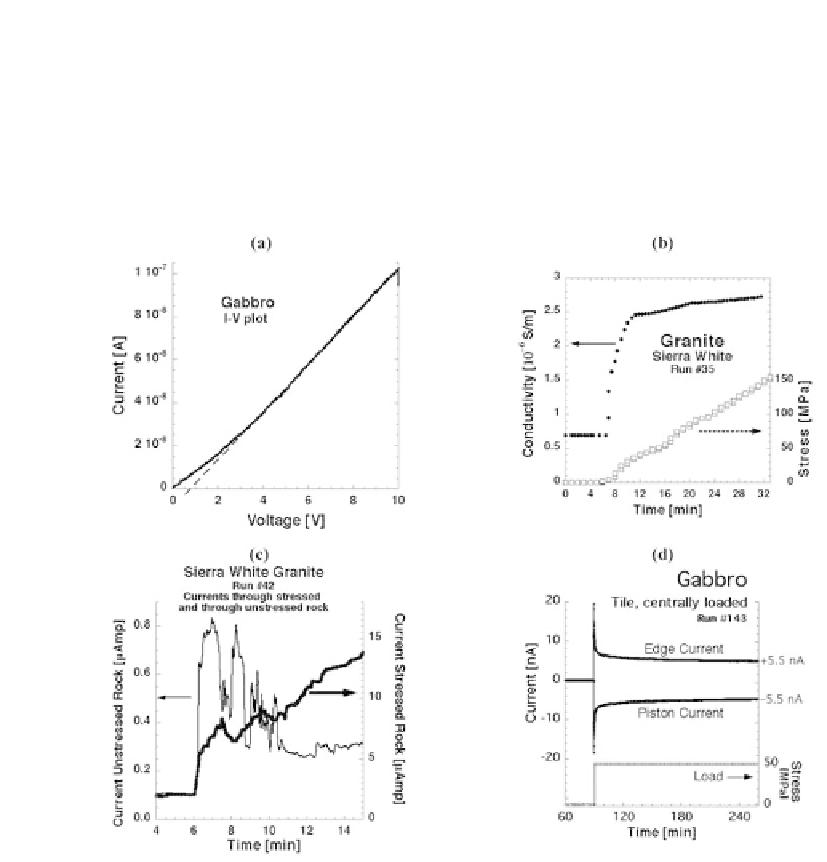

Figure 2.

Exemplary results obtained with dry rocks using the four different circuits depicted in

Figures 1a-d. (a) current-voltage plot indicating essentially a classical ohmic behavior; (b) significant

increase in the electrical conductivity when stress is applied and strongly non-linear current response;

(c) bold line: conductivity changes during application of stress through the stressed rock volume; thin

line: instant change in the electrical conductivity of the unstressed rock; (d) demonstration of the

stressed rock volume turning into a battery (see text).

To fi nd out more about this “cross talk” we used the circuit in Figure 1d where

we simply run a wire from the pistons at the center to the Cu contact along the edges.

Initially no current fl ows. When a load is applied to the center, both ammeters in the

circuit record a current as shown in Figure 2(d). The fi rst ammeter records electrons

fl owing from the pistons to ground. The second ammeter records electrons fl owing

from ground into the rock. The two currents are of the same magnitude, suggesting

that they are in fact the same current.