Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

pline, while much of the subject's popularity in schools is due precisely to its focus

on human-environment interactions. Yet the reality is that for most academic geog-

raphers 'environmental geography' is a small and often pretty elusive thing com-

pared with the dominant human and physical wings of the discipline. (It may also

be less familiar to North American readers where environmental geography has

maintained more of a central role in some departments and topics, following for

example, the traditions of human-environment geographers such as Carl Sauer or

Gilbert White.)

One impetus for this topic is to raise the profi le of environmental geography both

within and beyond the discipline. The environment is now widely touted as one

important reason for 'Rediscovering Geography', to quote the title of a US National

Academy of Sciences (1997) report on the future of geography. Echoing such calls,

Billie Lee Turner (2002; cf. Zimmerer, 2007) is just one of a number of prominent

fi gures urging geographers to embrace their long-ignored human-environment tradi-

tion so as to revitalise the discipline and secure its historically precarious place in

the academy. Environmental geography, according to this way of thinking, provides

a unifying link holding the two parts of the discipline together. It promises to make

good on the integrative vision of geography celebrated by Mackinder, Davis and

Ratzel but foiled as the discipline has become progressively more segmented and

specialised since the Second World War.

While we certainly support those aspirations, they will only be achieved by over-

coming three misconceptions about environmental geography. The fi rst is about its

place in the discipline of geography. Though environmental geography is often

understood as a sort of middle ground between human and physical geography, this

greatly oversimplifi es the shape of the discipline and thus the problems we face in

forging closer bonds of collective connection, collaboration and solidarity among

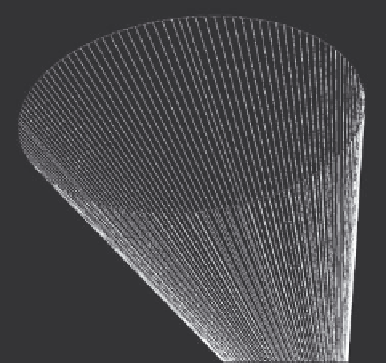

its various parts and branches. Rather than thinking about geography divided hori-

zontally between human and physical geography, we also need to recognise that the

heterogeneity within those very broad divisions means they are also stretched out

in the vertical dimension (fi gure 1.2), as indeed in a third temporal dimension of

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY

HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Ecology

Hydrology

Geomorphology

Quaternary

Climatology

Economic

Political

Social

Cultural

Historical

Figure 1.2

The multidimensionality of disciplinary divides in geography.