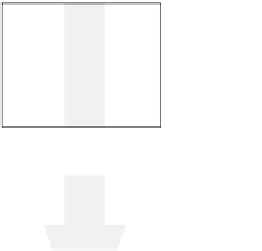

Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

Ecological

Heterogeneity

Ecological

Responsiveness

Ecological

embeddedness

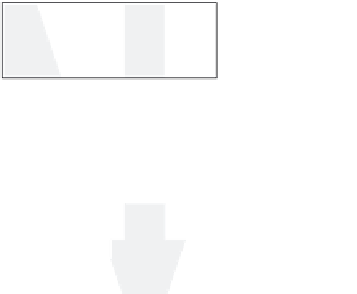

Uniform

Changing

Insensitive

Long-

term

Isolated

1. A general

understanding of the

physical environment as

it affects the

availabilities of natural

resources to human

society.

3. An understanding of changes in

the physical environment as they

affect the availabilities of natural

resources to human society.

6. An understanding of the mid- to long-term impacts

of human resource extraction on ecological feature's

productivity, diversity…etc.

5. An understanding of the short-term impact of the human

resource extraction on an ecological feature in interaction with

on-going ecological and climate dynamics

7. An understanding of the

indirect effects of human resource

extraction on other ecological

features and processes that are

influenced through ecological

relations with directly-impacted

ecological feature.

2. Anunderstanding of the

distributions of natural resources

that are differentially available to

the members of human societies

4 An understanding of the short term

impact of human resource extraction

on an ecological feature which is

directly affected (trees and

deforestation).

Variable

Static

Sensitive

Short-

term

Embedded,

interactive

Ecological

Dynamics

Temporal Scale

of Response

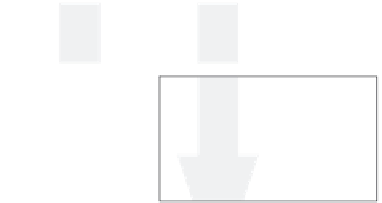

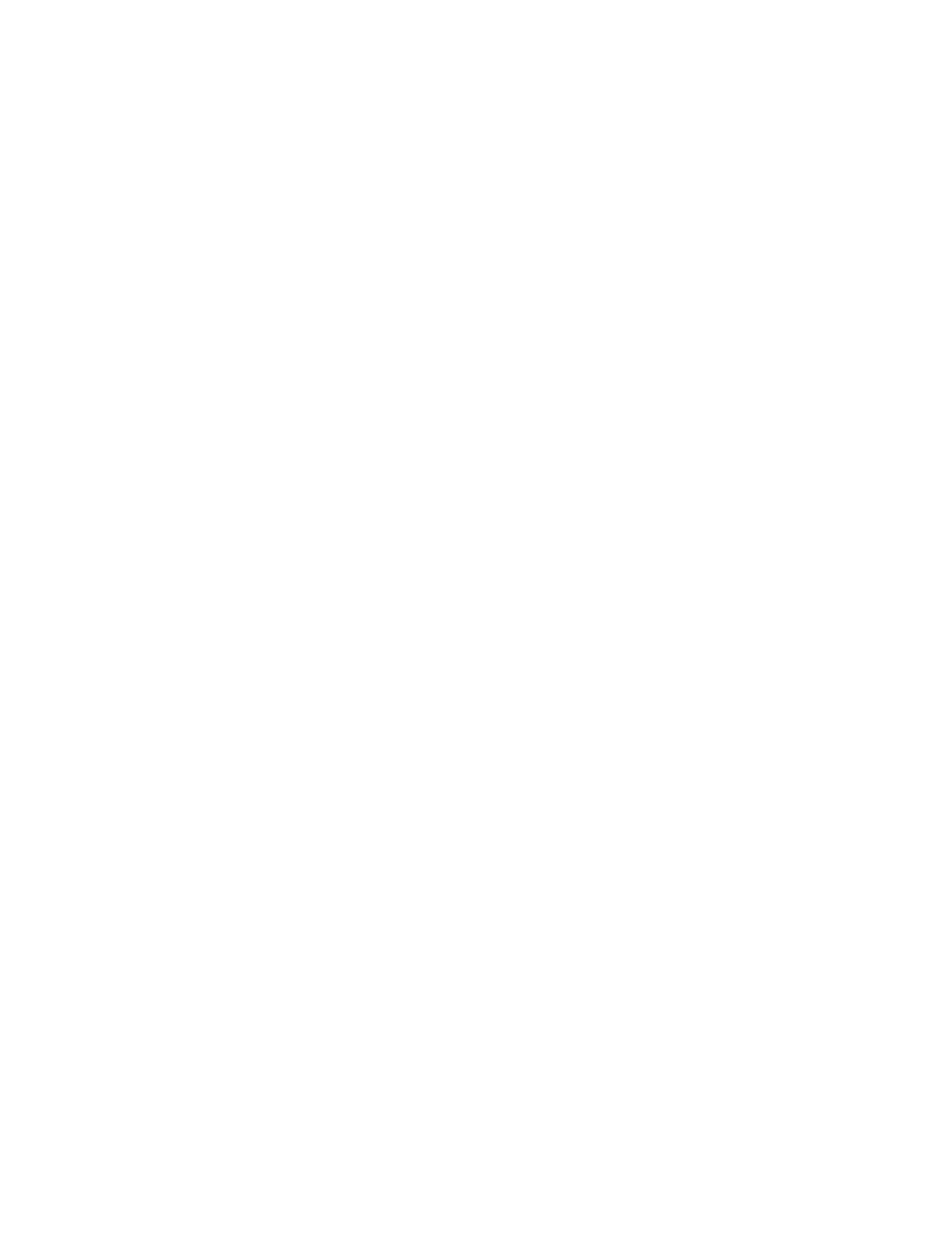

Figure 12.1

Levels of engagement with the complexity of ecological relations (1-7)

across fi ve dimensions of conceptual difference: ecological heterogeneity, dynamics,

responsiveness (to human actions), temporal scale and the degree to which the eco-

logical feature is seen as embedded within a broader set of relations.

questions. In so doing, the discussion below cautions against a naïve embrace of

the complex web of social and ecological relations by the 'big-picture' analyst - such

experiments will generally lead to ideographic descriptions or violent reductions of

complexity through various forms of systems analysis. At the same time, the discus-

sion cautions against knee-jerk invocations of the incommensurate epistemologies

of social and ecological analysis - thus sparing the political ecologist from moving

into uncomfortable ontological/epistemological spaces that run across and through

people-environment relations. This position does not derive from monistic vision

but an embrace of the analyst's agency. While diffi cult, we, as analysts, can place

different logics and epistemologies in parallel looking at congruencies and diver-

gences without being captured by any one. It is such integrative work where argu-

ably many advances in people-environment study will come - including those from

within political ecology.

It is important to recognise at the outset that engagement with ecological relations

is not without costs. Political ecologists may not have the necessary training or time

to perform ecological research themselves or the contacts or inclination to collabo-

rate with biophysical scientists. These costs are important and have worked to shape

the questions posed by political ecologists performing social-ecological change

research. An important but unexamined cost of greater engagements is how they

complicate the exposition of research results. While political ecologists seek to

provide richer and more complex narratives than simple declensionist or cornuco-

pian story lines, adding both ecological and social complexity may place too many

demands on a tractable story line. If we treat ecological and social systems as open,