Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

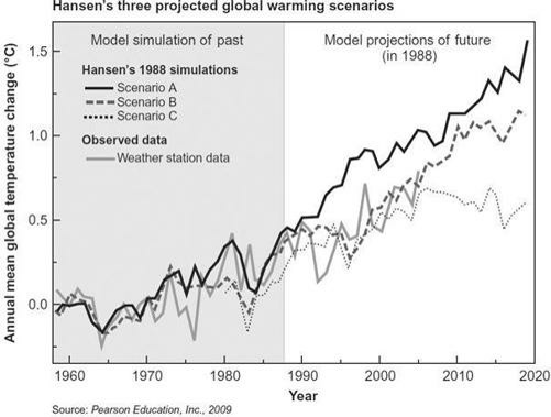

Figure 2.3: Testing Climate Models

A comparison of three different simulations of global warming through 2020 made by James Hansen in 1988. The curve made up of

weather station observations (available through 2005 in this analysis) closely matches the curve of the middle scenario (B)—the one that

is based on the trajectory of an emissions scenario that most closely matches actual greenhouse gas emissions over the preceding twenty

years. The upper and lower curves correspond to scenarios A and C, which assume higher and lower emissions respectively.

So the case could be made by the mid-1990s—in just five easy steps—that human activity was

changing our climate. The case became stronger over the next decade and a half as increasingly more

sophisticated models were developed and a wider array of data was collected that confirmed

unprecedented changes taking place in our climate. It is fair to say, though, that even by the mid-1990s

there was no longer reason for real scientific debate over the proposition that humans had warmed the

planet and changed the climate. That conclusion was now supported by the efforts of thousands of

scientists around the world whose work contributed to the various pillars of evidence detailed above.

What scientists were still debating with each other at scientific meetings and in the professional

journals was the precise balance of human versus natural causes in the changes observed thus far, and

just what further changes might loom in our future.

Answers to these more specific questions were far less clear. Climate scientists could surmise

that if human civilization continued to follow its current upward trajectory of fossil fuel burning, we

would likely see a near doubling of preindustrial atmospheric CO

2

levels by the mid-twenty-first

century. Furthermore, we could estimate that such an increase would lead to an additional warming of

anywhere between 1.5 and 4.5°C (roughly 3-8°F).

The large spread in estimated temperature increase arose primarily from uncertainty about the

effects of so-called feedbacks, responses of the system that can either further amplify or diminish the

warming. Certain feedbacks are almost certainly positive, amplifying the given effect; for example, a

warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor, and water vapor is itself a greenhouse gas, further

warming the surface. The melting of ice as Earth warms exposes more of the ground and ocean

surface. These surfaces absorb sunlight more effectively than does ice, which further amplifies the