Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

environmental ranges for their occurrence (e.g.

Potts & Jacobs 2003; Chapter 9), but these ranges

cover a variety of corals, some of which have

variable ways of obtaining energy and some of

which are adapted for variable conditions.

10.2.3.1 Tide-influenced shelves

Tidal forces affect the whole globe, but their influ-

ence on the world's oceans is heavily modified

by the bathymetry of the continental shelves and

by the shape of the coastlines. Tides may occur

daily (diurnal) or twice-daily (semi-diurnal): for

most places around the world, the semi-diurnal

tide is dominant. The dynamics of many contin-

ental shelves are dominated by tides, especially

where tidal ranges are high (Chapter 1), but even

in areas of low tidal range, tidal currents can be

strong locally, for example in the Torres Strait,

Australia (Harris 1989, 1991) and the Hayasui

Strait, Japan (Mogi 1979). On most shelves,

the flood and ebb current directions are gener-

ally opposed, but as they change in speed they

also change direction, so that, overall, the tide

describes an open ellipse, with a net direction and

magnitude (Stride 1982). Should the threshold

for bed sediment transport be exceeded by one

or both of the tidal currents, net bed sediment

transport results. Over long periods, the result

is a pattern of regional bed-sediment-transport

pathways, which begin at bed sediment 'parting

zones', where they tend to be associated with lag

surfaces, and end at bed sediment 'convergences',

where there is an accumulation of sandy sedi-

ment. On the UK shelf, individual transport

10.2.3 Sediment accumulation processes and

disturbance events

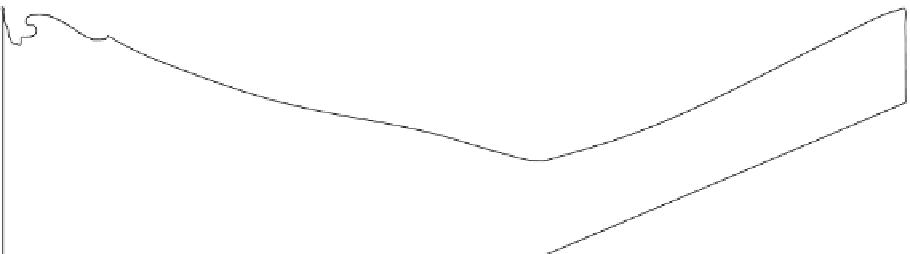

The wide distribution of modern continental

shelves means that, as a group, they experience

a range of environmental processes (Fig. 10.3)

and thus contain a diverse group of depositional

environments. The energy required to trans-

port sediments can be derived from a number

of sources. In most cases, the dominant energy

supply is either tidal or weather-related, al-

though there is generally a mixture of both. It is

also important to consider the relative impact of

daily (generally low-energy) versus episodic high-

energy phenomena (e.g. hurricanes, tsunami).

Finally, there are very well-developed models

of across-shelf transport (e.g. Fig. 10.5), but it is

now acknowledged that, for most shelves, the

along-shelf component of sediment transport is

greater than that across-shelf, especially where

the coastline (or shallow bathymetry) is relatively

straight (e.g. Great Barrier Reef shelf, Otago

shelf, Texas-Louisiana shelf, this chapter).

Wind-driven along-shelf flows

Estuary

Estuarine

plume

10

Int

e

rnal waves

20

Physical and

biological mixing

of sediment column

30

40

Steep gradients in

cross-shelf sediment flux

Inner shelf Mid-shelf

Fig. 10.5

Processes of cross-shelf transport. (Adapted from Nittrouer & Wright 1994.)