Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

that over 80 per cent of pollutant particles are

washed into a drainage system within the first 6-10

mm of rain falling (D'Arcy

et al

., 1998), and often

from a very small collection area within the urban

catchment (Lee and Bang, 2000). This information

is important when proposing strategies to deal

with the urban pollutant runoff. One of the main

methods is to create an artificial wetland within an

urban setting so that the initial flush of storm

runoff is collected, slowed down, and pollutants

can be modified by biological action. Shutes (2001)

has a review of artificial wetlands in Hong Kong,

Malaysia and England and discussed the role of

plants in improving water quality. Scholes

et al

.

(1999) showed that two artificial wetlands in

London, England were efficient in removing heavy

metals and lowering the BOD of urban runoff

during storm events. Carapeto and Purchase (2000)

reported similar efficiency for the removal of

cadmium and lead from urban runoff.

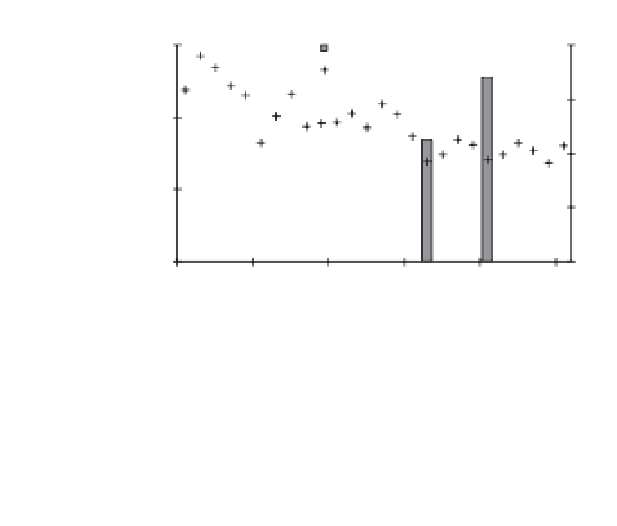

600

0.8

Permeable area

BFI

0.6

400

0.4

200

0.2

0

0

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

Figure 8.12

Baseflow index (BFI - proportion of annual

streamflow as baseflow) with time in a small catchment

in Auckland, New Zealand where there has been steady

urbanisation. The vertical bars show area of permeable

surfaces estimated from aerial photographs at 4 times.

Source

: Data courtesy of Auckland Regional Council

caused by an increase in the stormflow and total flow

and the actual amount of baseflow has stayed the

same. Whichever way, there has been a change in

the hydrological regime that can probably be

attributed to the rise in permeable surfaces as a

result of urbanisation.

River channelisation

It is a common practice to channelise rivers as

they pass through urban areas in an attempt to

lessen floods in the urban environment. Frequently,

although not always, this will involve straighten-

ing a river reach and this has impacts on the

streamflow. Simons and Senturk (1977) list some of

the hydrological impacts of channel straightening:

higher velocities in the channel; increased sediment

transport and possible base degradation; increased

stormflow stage (height); and deposition of material

downstream of the straightening. The impact of

urban channelisation is not restricted to the chan-

nelised zone itself. The rapid movement of water

through a channelised reach will increase the

velocity, and may increase the magnitude, of a flood

wave travelling downstream. Deposition of sedi-

ment downstream from the channelised section may

leave the area prone to flooding through a raised

river bed.

Pollution from urban runoff

There is a huge amount of research and literature

on the impacts of urbanisation on urban water

quality. Davis

et al

. (2001) link the accumulation of

heavy metals in river sediments to urban runoff,

particularly from roads. Specific sources are tyre

wear and vehicle brakes for zinc, and buildings for

lead, copper, cadmium and zinc (Davis

et al

., 2001).

In Paris, Gromaire-Mertz

et al

. (1999) found high

concentrations of heavy metals in runoff from roofs,

while street runoff had a high suspended solids and

hydrocarbon load. The hydrocarbons are of particu-

lar concern, especially the carcinogenic polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) derived from petrol

engines. Krein and Schorer (2000) trace PAHs from

road runoff into river sediments where they bind

onto fine sand and silt particles.

The nature of urban runoff (low infiltration and

rapid movement of water) concentrates the pollu-

tants in the first flush of water. Studies have shown