Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

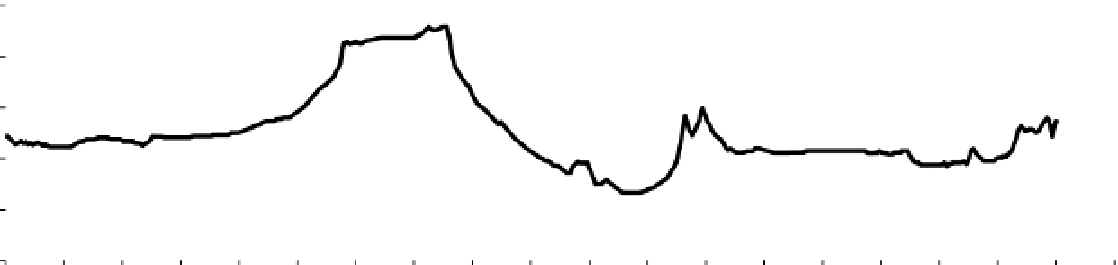

Modern

Laramie

River

floodplain

Dissected

bench with

Pleistocene

overwash

Little

Laramie

River

terrace

Modern Little

Laramie River

floodplain

Pleistocene

floodplain-

Airport Bench

Eolian deflation

basin-

Big Hollow

Dissected

bench

Laramie River

terrace

7,500

7,400

7,300

7,200

7,100

Northwest

Southeast

7,000

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

Distance along profile, feet

Riparian

Upland

grassland

Not

vegetated,

playa

Irrigated

hayland

Upland

grassland

Riparian

Upland

grassland

Upland

grassland,

hayland

Upland

grassland

Fig. 17.15. Seventeen-mile profile across the Laramie Basin

with topographic features and land cover indicated. As

shown in figs. 17.1, 17.3, and 17.7, this long profile extends

southeastward from the Little Laramie River, where a mosaic

of riparian woodlands, shrublands, meadows, and irrigated

hayland can be found. Grasslands are found over most of the

upland, across the Airport Bench, and down the slopes to near

the bottom of Big Hollow, where a playa with an ephemeral

pond has formed. there is no drainage from Big Hollow, but

standing water is rare because of low precipitation and no

streamflow. the Airport Bench is a remnant of the valley

floor at an earlier phase in the excavation of the basin and

has a surface that has been armored by coarse river cobbles

deposited during the Pleistocene. From the Big Hollow playa

southeastward, grasslands are found on the slopes and top

of a dissected bench. Beyond that, the former floodplain of

the Big Laramie River, known as a terrace, has a mosaic of

grasslands, shrublands, and irrigated hayland. Several lakes

also are located in this area. Riparian vegetation is found in

the current floodplain of the Big Laramie River. the profile

terminates on the dissected margins of a third, more ancient,

erosion-deposition surface. the Harmony Bench, illustrated in

fig. 17.5, does not occur along this profile. Plant species com-

position is influenced by topography, varying soil characteris-

tics, and exposure to wind.

sources of water and railroad stockyards (fig. 17.17).

Wolves were eradicated, enabling coyotes to become

more abundant. Prairie dog densities declined; down-

cutting of stream channels accelerated.

equally profound change resulted from the establish-

broad floodplains of the Big Laramie and Little Laramie

rivers enabled flood irrigation (see figs. 17.1 and 17.7).

Dams, canals, and ditches eventually were developed,

including the Wheatland reservoirs on the Laramie

River. Some of this irrigated land, though a small pro-

portion of the basin floor, was originally tilled for crops,

eliminating the native vegetation, but this practice soon

proved uneconomical because of the cool, short grow-

ing season. Livestock production prospered; irrigated

hayland—now with mostly introduced species—became

a valuable commodity.

irrigation had two general effects. First, it disrupted

the streamflow patterns of the rivers and creeks, reduc-

ing flood peaks in the spring and emptying many

streams by late summer, when irrigation water was in

greatest demand. Second, it enlarged the area of land

that was flooded. essentially all floodplains and some

adjacent uplands were altered by this practice. in gen-

eral, native riparian woodlands and shrublands exist

today only on land that was too wet for domestic use,

or where the presence of native plants provides benefits

appreciated by the landowners, such as shade for live-

stock, erosion control, shelter for homes and barns, or

habitat for fish and wildlife.

today the glint of numerous lakes across the basin is

especially obvious at sunset from the crest of the Lara-

mie Mountains—all more or less permanent because of

their connection to irrigation systems and providing

Search WWH ::

Custom Search