Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

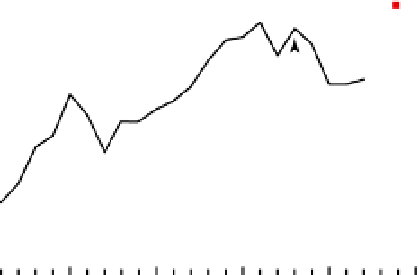

Northern Yellowstone Elk Herd

25

20

15

1988

Fires

1995

Wolf

reintroduction

10

5

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

YEAR

Fig. 15.13. Population trends in the northern Yellowstone

elk herd from 1971 to 2010. Beginning in 1968, the park

ended its program of artificially controlling elk numbers.

For that reason—and because of a series of moderate winters

and low levels of predation—the population grew. Large fires

burned approximately a third of the park in 1988, including

much of the northern winter range, and wolves were reintro-

duced to the park in 1995 after nearly a century of absence.

the recent decline in elk numbers is due to several factors, as

discussed in the text. three sets of data are shown (black and

red points): Schullery and Whittlesey (1992) for 1971-1992

(black); Vucetich et al. (2005) for 1985-2004 (red), and the

Yellowstone center for Resources (unpublished) for 2005-

2010 (red). the data overlap in the period 1986-1992 and

differ slightly, reflecting the difficulty in censusing wildlife

populations.

but they were generally ineffective in remote forested

areas. By the time a fire was reported and a crew found

it, often days later, the fire commonly had either gone

out or had become so intense that it could not be extin-

guished with hand tools. only with the availability of

new fire-fighting equipment after World War ii, notably

aircraft and smokejumpers, were managers able to sup-

press most ignitions.

in the wake of the 1963 Leopold report, researchers

began reporting that fire was an important ecological

process in most western forests and rangelands and

that fire exclusion was leading to undesirable ecologi-

cal changes. therefore in 1972—in the spirit of natural

regulation—park managers initiated a cautious pro-

gram of allowing lightning-caused fires to burn with-

out interference in a remote portion of the park during

moderate weather conditions, when the risk of human

injury or serious resource damage was minimal. in 1976

this natural fire program was expanded to encompass

most of the park's backcountry area. During a period of

15 years, from 1972 through 1987, a total of 235 light-

ning-ignited fires were allowed to burn, of which only

27 burned more than an acre; the largest burned 7,400

cessful, and similar natural fire programs were imple-

mented in surrounding wilderness areas and in Grand

teton national Park. However, in 1988 researchers and

managers learned that 15 years was not long enough to

fully understand the ecology of fire in the GYe.

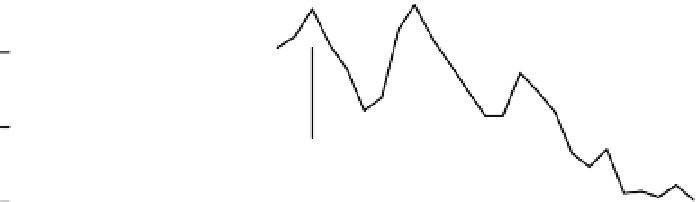

the summer of 1988 turned out to be one of the

driest and windiest on record. Some 248 fires were

ignited in the GYe by lightning or humans and burned

approximately 1.4 million acres (fig. 15.14). A massive

fire-fighting effort—25,000 fire-fighters and $120 mil-

lion—succeeded in minimizing loss of life and property

but could not stop the spread of fires across the land-

scape until significant precipitation finally arrived in

mid-September.

64

Park managers convened a panel of experts to eval-

uate the ecological impacts of the fires and to predict

likely ecosystem responses and management implica-

of the fires were influenced more by drought and wind

than by fuels or previous management practices. they

noted that large and severe fires also had occurred in

shown that large fires have recurred in Yellowstone at

intervals of decades or centuries throughout most of

park but burned substantial portions of surrounding

Search WWH ::

Custom Search