Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

61

Spring-Summer

Te mperature

100

59

57

0

55

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

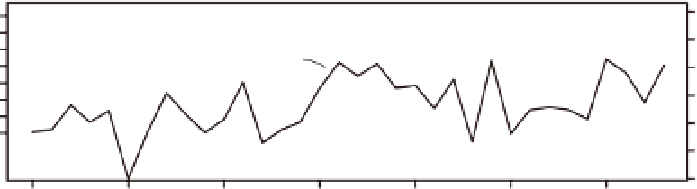

Fig. 12.15. trends in wildfire frequency and average spring-

summer temperature (March through August) in the western

United States since 1970. Fire frequency is the number of fires

greater than 1,000 acres in size per year. temperature and

fire frequency are correlated, and both increased beginning

around 1985. climate models suggest these trends are likely

to continue during the twenty-first century. Adapted from

Westerling et al. (2006).

water would be seen only in years of average or above-

average precipitation, which may become infrequent.

Because the regrowth of high-elevation forests is slow

and such forests are highly valued for other reasons—

wildlife, recreation, and aesthetics—intensive harvest

may not be a socially acceptable strategy for increasing

water supplies. other approaches, such as improving

water conservation measures and augmenting water

storage facilities, may be more effective.

With regard to fires, an upsurge of large fires dur-

ing the past 25 years has already occurred across most

of western north America (fig. 12.15). in addition,

extensive bark beetle outbreaks are now a continental

this recent upswing in forest disturbance. one is the

extensive cover of dense, mature conifer forests that

developed during the twentieth century, when fires and

other natural disturbances were relatively infrequent,

and when human-caused disturbances (such as timber

harvest) affected only a small portion of the forested

land. Dense, mature forests generally are more sus-

ceptible to fire and insect outbreaks than are younger

or more open forests. it is tempting to attribute such

problems to inadequate forest management, that is, too

much fire suppression or too little timber harvesting.

However, the increase in fire and bark beetle activity

is almost ubiquitous, occurring in forests with a great

variety of management histories throughout most of

the western and northwestern states and up into Alberta

and British columbia. climate change is the most likely

ditions favorable for beetles and fire will become more

frequent in the future.

Have Past Fires Increased the Probability of

Beetle Outbreaks?

For many years ecologists thought that fire-injured trees

provided loci for subsequent mountain pine beetle out-

breaks into surrounding unburned forests. the results

of one study in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem re-

vealed that the number of new adult beetles in the next

generation was greater in trees that sustained moderate

However, moderately injured trees are usually scarce

after fire in lodgepole pine forests, as most trees touched

by fire are severely injured and die. Few new adult

beetles emerge from the severely injured trees because

of various factors, including damage to the inner bark

tissues on which the beetles depend.

Drought or other nonfire stresses are more likely

initiators of mountain pine beetle outbreaks, simply

because they cause healthy trees to be more susceptible

to beetle attack without damaging the food resource

used by the beetle larvae. Also, in contrast to the moun-

tain pine beetle, spruce beetle outbreaks are known

to begin in windthrown timber or large-diameter log-

ging slash—though drought or other conditions that

stress living trees are necessary to sustain a widespread

outbreak.

65

Do Beetle Outbreaks Increase the Probability of Fire?

After a beetle epidemic, forests are mostly reddish-

brown or gray and they appear alarmingly flammable.

Research suggests that this association is not as simple

as it seems. Jeffrey Hicke and his colleagues from the

University of idaho developed a model that character-

Search WWH ::

Custom Search