Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

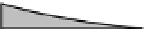

Fig. 12.13. Predicted long-term trends

in coarse wood after natural fire (top)

or clearcutting (bottom) in lodgepole

pine forests. time progresses from left

to right in these diagrams. natural

fires have occurred at centuries-long

intervals in these forests. thus, only a

single disturbance is shown in the top

panel. the bottom panel depicts a 100-

year clearcutting rotation, illustrating

how repeated harvest leads to a gradual

depletion of large pieces of wood (more

than 3 inches in diameter) and possibly

to changes in the amount and charac-

teristics of soil organic matter. Adapted

from tinker and Knight (2004).

Fire

Coarse wood created

by disturbance

Pre-disturbance

Coarse wood

Coarse wood added

by developing stand

Initial Clearcut

Coarse wood created

by disturbance

Pre-disturbance

Coarse wood

Subsequent clearcuts

a fire, many nutrients formerly tied up in the living and

dead biomass exist in the form of ash, which can be car-

ried away by water and wind; some are lost in smoke as

well. Warmer daytime soil temperatures resulting from

removal by fire of the cover of insulating litter also

stimulates soil microbial activity, including the bacteria

and fungi that decompose dead roots and other organic

matter, thereby accelerating nutrient release. thus, the

potential exists for considerable nutrient loss after a fire.

in contrast, aside from nutrients lost by erosion along

roads, the nutrient loss from harvesting is more likely

to be less than that following an intense fire, simply

because the harvested wood has surprisingly little nutri-

ent content compared to the slash that is left behind.

Unless the slash is piled and burned, the nutrients in

the slash are released slowly during decomposition,

reducing the likelihood of nutrient losses to streamflow.

Some of the most important differences between

clearcutting and fire have to do with the dead trees left

by fire—the same trees that would have been harvested.

Dead standing trees provide habitat for many organisms

tion of wood fragments to the soil enhances nutrient

availability and water-holding capacity and creates an

important substrate for microbial organisms. As com-

monly noted, the character of forest soils today is par-

tially the result of organic matter additions from wood

and leaves over the past 10,000 years or more (fig. 12.13).

Some wood is lost to periodic forest fires, but between

fires wood-derived organic matter gradually accumu-

lates. clearcutting interrupts these inputs, especially if

Search WWH ::

Custom Search