Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

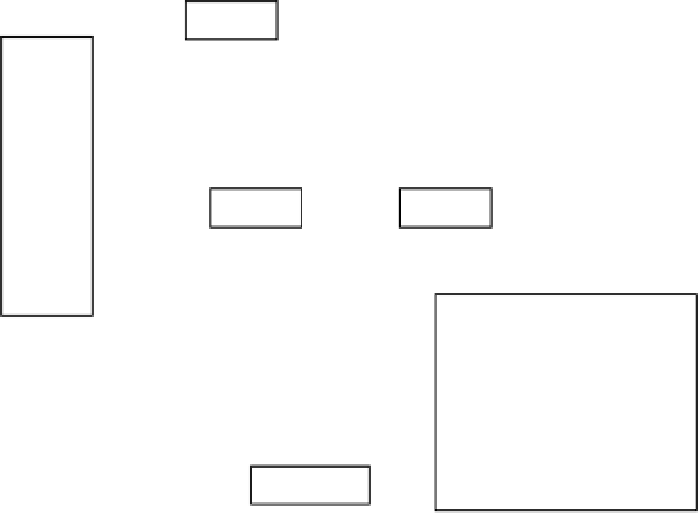

Transpiration

SOLAR RADIATION

Atmosphere

Photosynthesis

Heat

Herbivores

Leaves

Carnivores

Evaporation

to atmosphere

Fruit

Seeds

Omnivores

Rain

Snow

Surface

runoff

Nitrogen

fixation

Stems

Detritus

D

etritivores

Soil surface

Roots

Mycorrhizae

Herbivores

Carnivores

Soil organic

matter

Soil

solution

Omnivores

Mineral

soil

Decomposers

Subsurface

runoff

Weathering

Conservation Biology

Fig. 1.6. Major components (indicated by boxes) and interac-

tions (arrows) of a terrestrial ecosystem. Arrow width indicates

the relative amount of energy or water moving along a path-

way. temperature, water and nutrient availability, and grow-

ing season length determine the rates of transfer between

components. the irregular shapes indicate sources of water

and nutrients. complex food webs exist above and below the

soil surface, both of which are linked by the organic matter

on the soil, known as detritus, litter, or mulch. Such simple

diagrams do not convey the complexity caused by the diverse

group of organisms represented by each box. changes in one

component or process cause changes in others.

As for ecologists, conservation biologists can take sev-

eral approaches to their research. in general, they are

experts on rarity and what, if anything, can be done

about it. Some species are rare because their habitat has

been degraded by human activity; others are naturally

rare and are found only in one or a few small areas. Ulti-

mately, conservation biologists work to facilitate sound

management programs that lead to the maintenance or

recovery of threatened species, thereby reducing the need

for the strict mandates of the endangered Species Act. in

Wyoming, seven plants, six mammals, six birds, six fish,

and one amphibian are currently protected by federal law

or are under consideration for protection (figs. 1.7-1.9). 1.7-1.9).

others are of special interest because they are endem-

along with those that are common and widespread, and

all the varieties in each species—compose the biological

diversity of an area.

the conservation of rare and endangered species

requires information gained by scientists in ecology as

well as other disciplines. More specifically, biologists

with expertise in evolution and species identification are

needed to verify that so-called rare species are verifiable

species and are indeed rare. Some of them are difficult to

Fig. 1.5. (left) Major vegetation types plus cultivated

land, lakes, reservoirs, and urban and industrial develop-

ments. Sagebrush-dominated shrubland is most widespread

(33 percent of the land area), followed by mixed-grass prairie

(18 percent) and lodgepole pine forest (7 percent). Some

categories are not shown, because they occur in patches too

small for the scale of this map. these include most riparian

woodlands, shrublands, and meadows; most subalpine mead-

ows; most aspen groves; small woodlands of ponderosa pine

and limber pine; woody draws; playas with greasewood; small

cultivated fields; white spruce groves in the Black Hills; and

foothill grasslands and shrublands. Subheadings indicate as-

sociated species in the foothills (fh), the Greater Yellowstone

ecosystem (gye), the Black Hills (bh), and the Sierra Madre

(sm). Adapted from the national land cover map (2011) of the

U.S. Geological Survey Gap Analysis Program. Land cover

percentages are from Driese et al. (1997). cartography by Ken

Driese.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search