Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

(such as the red squirrel and red-backed vole) commonly

graze on mushrooms, truffles, and puffballs, the repro-

ductive structures of fungi that decompose the detritus,

and birds commonly prey on these small mammals and

various invertebrate detritivores. Moreover, evidence

suggests that these animals are important in dispersing

the spores of fungi, which in turn are important not

only for decomposition but—in the case of mycorrhizal

fungi—also for the establishment and growth of new

plant seedlings, including those of all Rocky Mountain

the importance of mycorrhizal fungi is suggested

by estimates that up to 15 percent of the net primary

productivity in a coniferous forest goes to the main-

indicate that, rather than being parasites, mycorrhizal

fungi develop a mutually beneficial association with

the form of carbohydrates, while the fungal filaments,

known as hyphae, extend beyond the roots and enhance

water and nutrient uptake. the decaying biomass of the

fine roots and associated fungi may contribute more to

nutrient availability than do decaying leaves, twigs, and

branches.

on average, only 2 percent or less of the energy fixed

by plants during photosynthesis flows through animals

in terrestrial ecosystems, whether forests, shrublands, or

grasslands, yet animals often influence the ecosystem

in important ways. An example is the planting of white-

bark and limber pine seeds by clark's nutcracker (see

chapters 10 and 11). the populations of different her-

bivores and carnivores continually fluctuate, with the

result that their influences are greatly amplified when

they are abundant, such as during outbreaks of bark

beetles. A less well-known example occurs when the

populations of porcupines are high. Porcupines feed on

tree bark, resulting in reduced flow of carbohydrates to

the roots, which lowers plant growth in the forest as a

changing over time, as does the amount of energy flow-

ing through the detrital, grazing, and fire pathways.

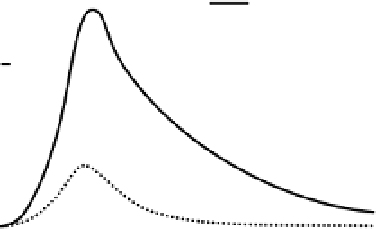

3

Live trees

Forest floor litter

Dead trees and

downed wood

2

1

0

-1

-2

0

40

80

120

160

200

Stand Age (years)

Fig. 12.3. Rates of biomass increment or decline in live trees,

forest floor litter, and dead trees and downed wood change

as forests grow to maturity and become “old-growth” forests.

older forests have more dead trees and downed wood, but

tree growth slows as forests age (see also fig. 12.1). Dead trees

and downed wood, sometimes referred to as snags and coarse

woody debris, decline soon after fire, as decomposition rates

of this material are relatively high when water and nutrients

are more readily available for the decomposers. the forest

floor litter increases initially after a fire—which commonly

burns much of the pre-fire forest floor—but then remains

about the same, as litterfall becomes approximately equal to

the rate of litter decay. the patterns illustrated will be some-

what different for forests growing on different soils, at differ-

ent elevations, or in different topographic positions. these

graphs are based on data collected from several lodgepole pine

forests at an elevation of about 9,500 feet in the Medicine Bow

Mountains. Rates of change are expressed as metric tons per

hectare per year; see fig. 12.1 for unit conversions. Adapted

from Pearson et al. (1987); see also Smith and Resh (1999) and

Kashian et al. (2013).

decomposition occurs under snow during the winter, as

some of the decomposers are able to function at the soil/

and is flammable when dry, fire is another important

pathway for energy flow—a decomposition process that,

like bacteria and fungi, releases the inorganic nutrients

required for new plant growth (fig. 12.4).

the combined biomass of forest floor litter, fungi,

and bacteria is far greater than the total biomass of

vertebrates and invertebrates. not surprisingly, various

animals have evolved to depend on detritus for a signifi-

cant part of their energy. For example, small mammals

Hydrology of Forest Landscapes

Mountain landscapes are hydrologically distinctive

from the surrounding lowlands, because they receive

Search WWH ::

Custom Search