Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

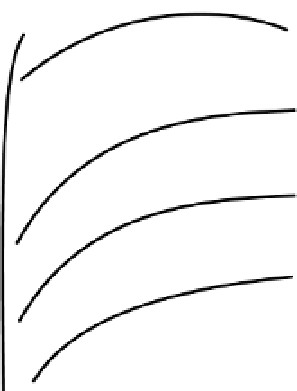

than might be expected based solely on elevation. Val-

ley bottoms are often cool because of cold-air drainage.

thus, species typically found high on the mountains

may extend to low elevations in ravines or on north

slopes with less direct sunlight, and species requiring a

warmer environment may be found at unusually high

elevations on south slopes (fig. 11.1).

Soils also have a pronounced effect on the landscape

mosaic. For example, meadows occur in the Bighorn

Mountains on comparatively dry, fine-textured soils—

even at high elevations where forests might be expected

(see chapter 12). Forests of Douglas-fir, lodgepole pine,

engelmann spruce and subalpine fir grow on other

kinds of soils (inceptisols and Alfisols), where moisture

stress is less severe in late summer (such as on north

slopes). Lodgepole pine is typically the most common

tree in forests on coarse, less fertile soils derived from

granite or rhyolitic lava. Multiple factors—soils, local

climate, influences of herbivores and pollinators, and

local history of disturbance and species migrations—

Surviving in the Mountains

Perhaps the primary challenge for plant survival in the

Rocky Mountains is the short, cool, and sometimes

dry growing season. Several distinctive adaptations are

involved. Most notable is that photosynthesis occurs

in montane plants at temperatures near freezing, or

or wintergreen (that is, they have chlorophyll in their

leaves or stems all year). the ability to tolerate low tem-

peratures, combined with the presence of chlorophyll

throughout the year, enables some plants to extend

their growing season into late fall and begin the next

one earlier in the spring. evergreen conifers are excel-

lent examples, but other plants have similar adapta-

tions. For example, such deciduous plants as aspen

and dwarf huckleberry have chlorophyll in their stems,

which permits photosynthesis even when they have no

leaves. the green stems of the huckleberry may account

for a substantial portion of the plant's annual photo-

deciduous evergreen plants.

Some shrubs and herbaceous plants have leaves

that remain green even under the snow—for example,

elk sedge and wintergreen. they are capable of photo-

synthesis and growth as soon as the snow is shallow

enough to permit light penetration, when the tempera-

thesis at cold temperatures is an important adaptation,

but simply being able to survive the cold is another. A

comparison of low-temperature tolerances of numerous

tree species found that, unlike the trees from warmer

climates, those of the Rocky Mountains could tolerate

temperatures of -76°F.

8

Another problem for mountain plants is acquiring

nutrients from infertile, coarse-textured soils. All of the

tree species have mycorrhizae (fig. 11.2), which are con-

centrated in the top 12 inches of the soil, where limiting

nutrients are most likely to be available. once incorpo-

rated into plant tissues, the nutrients are retained for

extended periods simply by the longevity of leaves and

twigs. Lodgepole pine needles, for example, persist for

5-18 years, depending on environmental conditions.

Fig. 11.1. Approximate distribution of different forest types in

relation to elevation and moisture availability. note that each

kind of forest typically occurs at the lowest elevation in cool,

moist ravines. Foothill shrublands occur just below wood-

lands and forests at lower treeline.

12000

3500

Alpine

Fellfield

9000

Turf

Wet

meadow

Spruce-fir

Lodgepole pine

Aspen

9000

3000

Willow

Aspen

9000

Lodgepole pine

2500

Willow

Alder

Birch

8000

Douglas-fir

or

Ponderosa pine

Aspen

7000

Cotton-

wood

Foothill

shrublands

2000

6000

Wet

valley

bottom

Cool

ravine

North

slope

E-W

slope

South

slope

Ridge

MOISTURE GRADIENT

Search WWH ::

Custom Search