Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

Similarly, Krueger found that pronghorn used prairie

dog colonies preferentially, perhaps because of a higher

number of forbs there.

50

Such interactions among bison, pronghorn, and

burrowing animals surely must have been widespread

prior to the arrival of europeans. Because of the prairie

dog and other burrowing animals, north American

bison may have been more abundant, along with their

predators (grizzly bears and wolves). one study found

more herbivorous insects on rangeland grazed by cattle

than on rangeland that had not been grazed for a long

period, and another study found more belowground

invertebrates in the soil of prairie dog towns than away

from the towns.

51

the effects of large herbivores have attracted the

attention of most grassland scientists, yet the effects of

the abundant belowground herbivores, small as they

are, should not be ignored. For example, in an experi-

mental study, a nematocide was applied to kill all the

Apparently, microbial grazers improve nutrient avail-

ability for vascular plants just as their much larger

aboveground counterparts do.

50

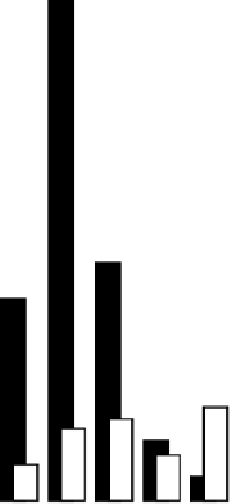

Cause of fire in 1960:

Human

Lightning

40

30

20

10

0

APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT

Fig. 6.10. number of recorded human- and lightning-caused

fires in the grasslands and shrublands of the Powder River

Basin north of Douglas, Wyoming, in 1960. Adapted from

Komarek (1964).

Fire

Prior to the advent of fire suppression, prairie fires

occurred frequently because of the highly flammable

leaves and stems that rapidly accumulate. Without fire,

and if grazing intensity is low, the standing biomass

is gradually flattened to become part of the mulch on

the soil surface. once fires were ignited, plumes of

smoke would have been visible. the fires would have

burned for weeks or months until extinguished by wet

weather, or until an effective fire break was reached

(such as a sufficiently wide river or ridge, or an area of

inadequate fuel to sustain the fire). Fires might have

been less common during extended droughts, largely

because of less fuel.

53

the source of ignition was usually lightning strikes,

which start fires in grasslands as they do in forests.

An annual average of 10-25 lightning-caused fires

per 1,000 square miles has been reported for differ-

been documented as the major cause of prairie fires

in the Powder River Basin north of Douglas (fig. 6.10).

Most occur during July and August, when fuels are

drier and thunderstorms more frequent. thunder-

storms may produce enough rain to extinguish such

fires, but lightning strikes with no or little rain are

common.

55

native Americans also started fires, sometimes

reviewed 145 historical accounts of fire by 44 observers

in the Rocky Mountain region. He concluded that fires

set by indians were most common in the lowlands and

that they could have been annual events in some areas

(although probably the same tract of grassland did not

burn in two consecutive years). For much of the Great

Plains, mean fire intervals were from 2 to 25 years, with

Grassland fires in central nebraska occurred at intervals

of 4-6 years from 1850 to 1900, and every 15-30 years

in western nebraska. Wyoming grasslands probably

burned less frequently owing to slower fuel accumula-

tion in a more arid climate (fig. 6.11).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search