Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

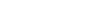

The ubiquitous nature of landslides is illustrated

with reference to the conterminous United States in

Figure 12.15. By far the most prevalent zone for

landslides occurs in the Appalachian Mountains in the

eastern part of the continent. Second in importance

are the Rocky Mountains, particularly in the states of

Colorado and Wyoming. The coastal ranges along the

Pacific Ocean form the third most hazardous zone. In

January 1982, heavy rains triggered more than 18 000

landslides in the San Francisco Bay region, causing

25 deaths and more than $US100 million in damage.

It was the third biggest disaster in this region after

the 1906 San Francisco and 1989 Loma Prieta earth-

quakes. The threat is even greater in the Los Angeles

region. Landslides in the Los Angeles area killed 200

people on 2 March 1938. In all, landslides in some

form affect about one-seventh of the United States.

While most of the failures happen in mountainous

areas, they are not restricted to these zones. The

Mississippi Valley has a low, but significant, risk, as do

plateaus on the southern Great Plains where weak

shales are found. The United States is not unique in

this respect. Landslides are a common geomorphic

process in most countries with steep or raised terrain.

rock cliff-faces but can occur in certain unconsolidated

sediments that permit vertical slopes to develop.

Generally, the vertical faces must be continually main-

tained by erosion of talus and screes that form at the

base of cliffs. If this debris is permitted to accumulate,

then the vertical face becomes buried. The debris is

removed through chemical breakdown, washing out of

fines and slippage. There is, thus, a balance between

the rate of cliff retreat controlled by the occurrence

of rockfalls, and the rate of removal of debris at the

base. The production of talus does not have to occur

catastrophically, but instead debris can simply accumu-

late through the continual addition of material as it is

loosened from the cliff-face by weathering, rainfall,

small shock waves, or frost action.

The preservation of a vertical face is dependent

upon the characteristics of the bedrock. Generally,

less resistant rock such as shales will not be able to

develop cliff-faces, because the rock is susceptible

to weathering and slippage. Situations where there are

massive beds of sandstone or limestone, or where these

resistant beds overlie weaker beds, are ideal for the

formation of cliffs. However, massive beds without

much jointing do not erode easily, and hence do not

produce rockfalls. For example, the escarpments along

the east Australian coastline have faces up to 100 m or

more high in places, and appear to be retreating at

rates as low as 1 mm yr

-1

without significant rockfalls.

Significant joints or vertical failure planes should also

Rock

falls

(Scheidegger, 1975; Voight, 1978)

Rockfalls are one of most rapid land-instability events.

They are generally restricted to unvegetated, vertical,

0

1000 km

Severest landslide

hazard

Moderate landslide

hazard

Localized landslide of

varying severity

Extent of landslides in the coterminous United States (after Hayes, 1981).

Fig. 12.15