Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

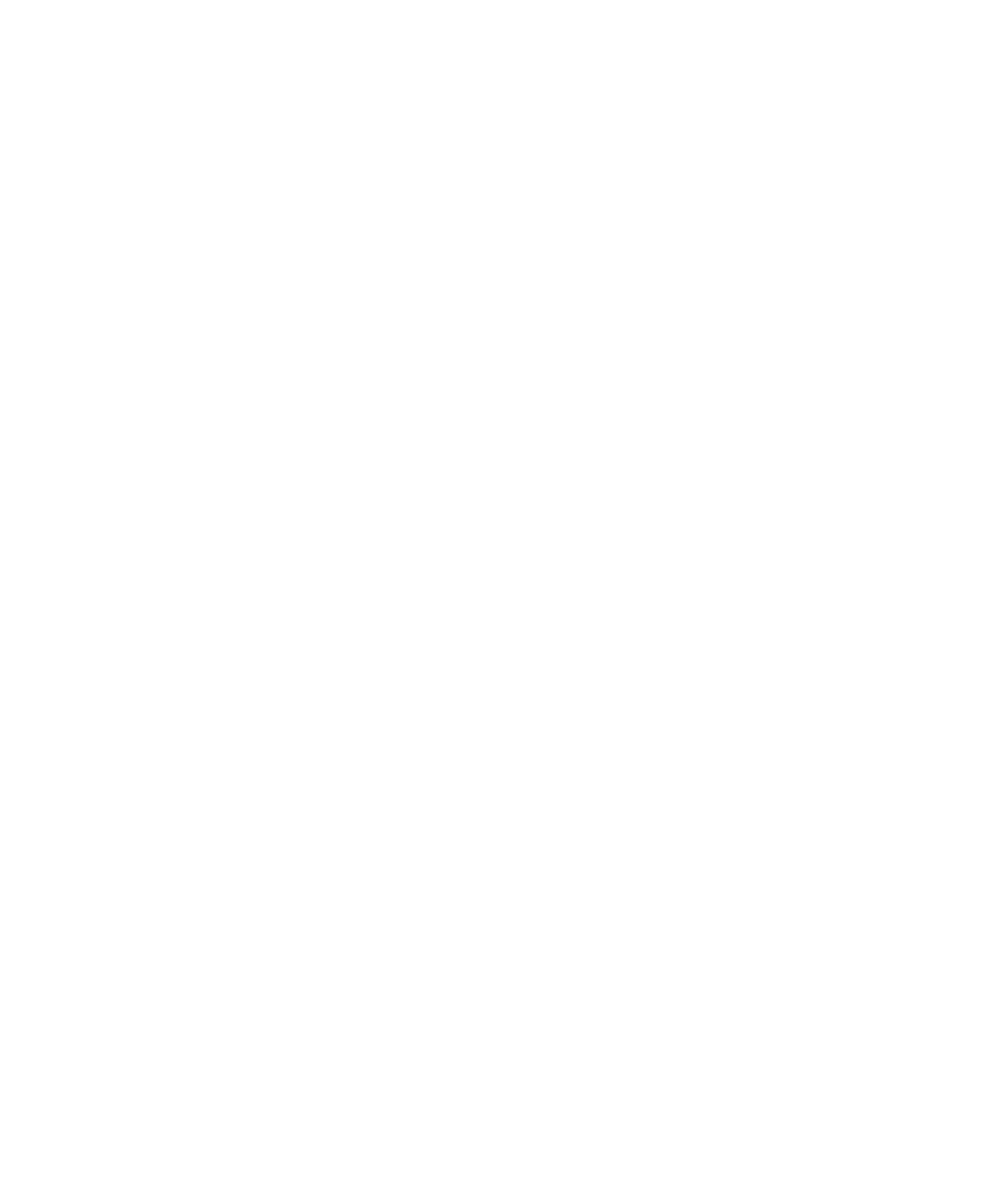

Naples

N

Herculaneum

Pompeii

Stabiae

Sorrento

Pyroclastic flow

Agropoli

0

10

20

30 km

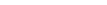

Location map of Mt Vesuvius (Blong, ©1984, with permission Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group, Australia).

Fig. 11.7

took three days before it was light enough to recover

his body. The pyroclastic ash falls buried Stabiae and

Pompeii to depths of 2 and 3 m, respectively. Most of

the residents of Pompeii appear to have fled, but

10 per cent were literally caught dead in their tracks by

the pyroclastic flows that climaxed the eruption. Her-

culaneum was also affected by the tephra fallout but, in

the latter stages of the eruption, was engulfed by a

mudflow 20 m thick. This lahar appears to have been

caused by groundwater expulsion as the caldera

collapsed.

The eruption marks one of the first volcanic disas-

ters ever documented. The sequence of events at

Vesuvius has been labelled a Plinian-type eruption

after Pliny's descriptions. Many of the buildings in

Pompeii and Herculaneum protruded above the ash.

The buildings were ransacked of valuables, dismantled

for building materials, and subsequently buried by

continued eruptions. The ash reverted to rich agricul-

tural land and Pompeii was forgotten. It was not until

1699 that Pompeii was rediscovered and excavated.

Vesuvius has continued to erupt aperiodically until the

present day. Subsequent major eruptions occurred in

203, 472, 512, 685, 787 and five times between 968 and

1037 AD. It then remained dormant for 600 years until

1630, when it produced extensive lava flows that killed

700 people. The last major eruption in 1906 produced

tephra up to 7 m thick on the north-east side of the

mountain. About 300 people were killed, mainly under

collapsing roofs. If the 79 AD eruption recurred today,

over 1 500 000 people would be affected.

Kra

katau (26-27 August 1883)

(Verbeek, 1884; Latter, 1981; Self & Rampino, 1981;

Nomanbhoy & Satake, 1995; Winchester, 2003)

The eruptions of Tambora and Krakatau in the

nineteenth century make Indonesia, with its dense

population, one of the most hazardous zones of

volcanic activity in the world. Krakatau lies in the

Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java, Indonesia

(Figure 11.8). The Javanese

Book of Kings

describes an

earlier eruption that generated a sea wave that

inundated the land and killed many people in the

northern part of Sunda Strait. Krakatau had last been

active in 1681 and, during the 1870s, the volcano

underwent increased earthquake activity. In May of

1883, one vent became active, throwing ash 10 km

into the air. By the beginning of August, a dozen

Vesuvian-type eruptions had occurred across the island.

On 26 August, loud explosions recurred at intervals of

ten minutes, and a dense tephra cloud rose 25 km

above the island. The dust particles formed nuclei for

water condensation and muddy rain fell on adjacent

islands. The explosions could be heard throughout the

islands of Java and Sumatra. In the morning and later

that evening, small tsunami waves 1-2 m in height

swept the strait striking the towns of Telok Betong on

Sumatra's Lampong Bay, Tjaringin on the Java coast