Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

Mt. Spurr

Redoubt

Augustine

Laki

Iceland

Kodiak Is

Vatnajökull

Surtsey

Katmai

Mt. Hekla

Vancouver

English Channel

France

Mt Rainier

Usu

Mt St Helens

Bandai

Santorini

Columbia River Plateau

Vesuvius

Mt. Etna

San Francisco

Mt. Stromboli

Mauna Loa

Hilo

Mt. Pinatubo

La Soufrière

Parícutín

Kilauea

El Chichon

Santa Maria

Mt. Pelée

Kolkata

Aden

Soufrière

Dieng Plateau

Kelat

Seychelles

Islands

Nevado del Ruiz

Krakatau

Galunggung

Mt. Agung

Tambora

Rift Valley

Elsey Cr.

Mauritius

Rodriguez Is.

Northwest Cape

Port Elizabeth

Lake Taupo

Mt. Ruapehu

Mt. Erebus

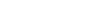

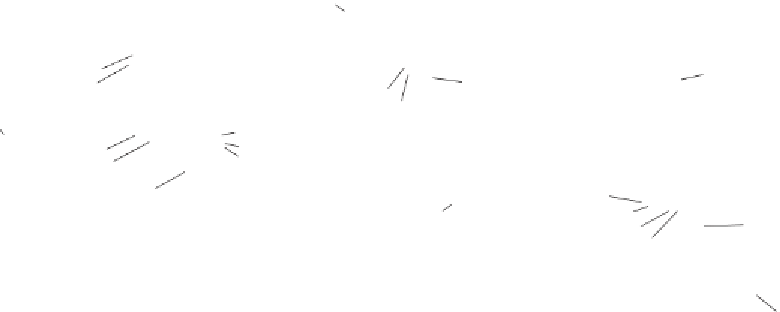

Location map.

Fig. 11.1

all major placenames mentioned in this chapter and

not located on individual site maps). By calculating the

amount of energy partitioned among these various

processes, it is possible to classify the type of volcano

and its magnitude. This is of little help in predicting

volcanic events, but it can give information on the type

of eruption that has occurred. For instance, eruptive

volcanoes expend considerable energy in easily

measured atmospheric shock waves and tsunami.

Knowledge of these values can be used to evaluate the

overall energy of the volcano. In addition, the contin-

ual monitoring of energy expenditure, and the way it is

partitioned, can be used to predict whether a volcano

is dying down or increasing in activity.

permit safe evacuation. In the geological past, some

volcanoes have had enormous magma chambers that

emptied and flooded landscapes over vast distances in

a short period. Some flood lavas have laid down

deposits 500 m thick over distances of 300 km. The

largest such deposits on Earth (flood lavas also occur

on other planets and their moons) make up the Deccan

Plateau in India, the island of Iceland, the Great Rift

Valley of Africa, and the Columbia River Plateau in

the United States. 'Hawaiian'-type eruptions are very

similar to flood lavas. However, at times, they can

produce tephra and faster moving, thin lava flows.

Hawaiian eruptions tend to be aperiodic, building up

successive deposits over time. These can form large

cones that, in the case of the Hawaiian Islands, can be

tens of kilometres high and hundreds of kilometres

wide at their base.

Explosive eruptions can be more complex. The

simplest form begins with the tossing out of moderate

amounts of molten debris. 'Strombolian' volcanoes,

named after Mt Stromboli in Italy, throw up fluid lava

material of all sizes. Most eruptions of this type toss out

bombs a few hundreds of metres into the air, rhythmi-

cally, every few seconds in events that can go on for

years. They can also produce moderate lava flows.

Strombolian volcanoes are characterized by a very

symmetrical cinder cone that grows in elevation

around the vent. Strombolian volcanoes also represent

an intermediate stage between basaltic and acidic

magma extrusions. 'Vulcanian'-type eruptions are more

TYPES OF VOLCANIC

ERUPTIONS

(Fielder & Wilson, 1975; Blong, 1984; Wood, 1986)

While most classification schemes refer to a specific

historical event characterizing an eruption sequence, it

should be realized that each volcanic eruption is

unique, and may over time take on the characteristics

of more than one type. There are two types of non-

explosive volcanoes. Volcanoes producing

flood lavas

are the least hazardous of all eruptions, because they

occur very slowly, permitting plenty of time for evacu-

ation. Flood lavas are basaltic in composition. At

present, such eruptions are rare, occurring only in

Iceland, where they happen with sufficient warning to