Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

Napoleonic Wars in 1812, San Francisco during the

1906 earthquake, and Dresden and Hamburg during

the Second World War. The outbreaks of fire were

minor to begin with, but they occurred throughout

both cities in large numbers, mainly because the

earthquake occurred at lunchtime when many open

fires were being used for cooking. Within half-an-

hour, over 200 small fires were burning in Yokohama

and 136 were raging in Tokyo. The rubble of collapsed

buildings in the streets and cracked water mains

compounded the difficulty in dealing with the fires.

Firefighters could neither get to the fires nor

obtain a reliable water source to extinguish them.

Once the fires raged, the cluttered streets hampered

evacuation. In Yokohama, 40 000 people fled to an

open area around the Military Clothing Depot, which

was subsequently engulfed in flames. All these people

died from the searing heat or suffocation caused by

the withdrawal of oxygen.

The spread of fire was aided initially by strong

tropical cyclone winds. In the chapter on tropical

storms, it was pointed out that the earthquake was

probably triggered by the arrival of a tropical cyclone

the previous day. The calculated change in load on the

Earth's crust because of the pressure drop, and

the increased weight of water from the storm surge,

was 10 million tonnes km

-2

. The fires were exacerbated

by the development of strong winds generated by the

cyclone in the lee of surrounding mountains. These

The

Japanese earthquake hazard

(Hodgson, 1964; Holmes, 1965; Hadfield, 1992; EQE,

1995; Bardet et al., 1997)

The most notable earthquake in Japan in the last

century occurred on 1 September 1923 in Sagami Bay,

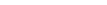

50 km south-west of Tokyo (Figure 10.8). Known as

the Great Kanto Earthquake, the crustal movements

twisted the mainland in a clockwise direction, with

a maximum horizontal displacement of 4.5 m and a

vertical drop of 2 m. Until the Alaskan earthquake,

these were some of the greatest crustal shifts

recorded. Within the bay itself, changes in elevation

were much larger owing to faulting, compaction, and

submarine landslides. Measurements after the earth-

quake indicated that parts of the bay had deepened by

100-200 m with a maximum displacement of 400 m.

The Tokyo earthquake immediately collapsed over a

half million buildings and threw up a tsunami 11 m in

height around the sides of Sagami Bay. However,

these events were not responsible for the ultimately

large death toll, because many of the collapsed build-

ings consisted of lightweight materials. The deaths

resulted from the fires that immediately broke out in

the cities of Tokyo and Yokohama, and raged for three

days, destroying over 50 per cent of both cities. The

fires rate as one of the major urban conflagrations in

history - on the same scale as fires that destroyed

London in 1666, Chicago in 1871, Moscow during the

Tokyo

2.0

Yokohama

2.7

Bozo

Peninsula

1.5

Epicenter

Fault displacement

Direction of

horizontal

movement (m)

Direction of

vertical

movement

Sagami Bay

2.0

2.7

2.7

Idzu

Peninsula

3.6

N

0

10

20

30

40

50 km

Distribution of faulting for the Tokyo earthquake, 1 September 1923 (from Holmes, 1965).

Fig. 10.8