Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

famine ensue. Requests for food from neighbors

customarily could not be refused, and relatives working

in cities were obligated to send money back to the

community or, in desperate circumstances, were

required to take in relatives from rural areas as

refugees.

A resilient social structure had built up over several

centuries before British colonial rule occurred in 1903.

Hausan farmers lived in a feudal Islamic society. Emirs

ruling over local areas were at the top of the social

'pecking order'. Drought was perceived as an aperiodic

event during which kinship and descent grouping

generally ensured that the risk from drought was dif-

fused throughout society. There was little reliance upon

a central authority, with the social structure giving

collective security against drought. Taxes were col-

lected in kind rather than cash, and varied depending

upon the condition of the people. The emir might

recycle this wealth, in the form of loans of grain, in a

local area during drought. This type of social structure

characterized many pre-colonial societies throughout

Africa and Asia. Unfortunately, colonialism made these

agrarian societies more susceptible to droughts.

After colonialism occurred in Nigeria, taxes were

collected in cash from the Hausan people. These taxes

remained fixed over time and were collected by a

centralized government rather than a local emir. The

emphasis upon cash led to cash cropping, with returns

dependent upon world commodity markets. Produc-

tion shifted from subsistence grain farming, which

directly supplied everyday food needs, to cash

cropping, which provided only cash to buy food. If

commodity prices fell on world markets, people had to

take out loans of money to buy grain during lean times.

As a result, farmers became locked into a cycle of

seasonal debt that accrued over time. This indebtedness

and economic restructuring caused the breakdown of

group and communal sharing practices. The process of

social disruption was abetted by central government

intervention in the form of food aid to avert famine.

Hausan peasant producers became increasingly vulner-

able to even small variations in rainfall. A light harvest

could signal a crisis of famine proportions, particularly if

it occurred concomitantly with declining export prices.

The Hausan peasantry now lives under the threat of

constant famine.

During drought, a predictable sequence of events

unfolds. After a poor harvest, farmers try to generate

income through laboring or craft activity. As the famine

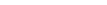

Senegal

Mauritania

Mali

30˚

Sudan

P

ort Sudan

Eritrea

Djibouti

Niger

Chad

20˚

10˚

Gambia

Nigeria

Ethiopia

Burkina

Faso

0˚

Somalia

Kenya

10˚

Semi-arid

Botswana

20˚

Sahelian

countries

Kalahari

Desert

30˚

Map of semi-arid regions and the Sahel in Africa.

Fig. 5.1

favorable for food gathering and hunting, !Kung clans

split into progressively smaller groups with as few as

seven people. During severe droughts, however, the

!Kung gathered in groups of over 200 at two perma-

nent water holes, where they attempted to sit out the

dry conditions until the drought broke.

In societies that are more agrarian, there is a critical

reliance upon agricultural diversification to mitigate all

but the severest drought. Pre-colonial Hausa society in

northern Nigeria (on the border of the Sahara Desert)

exemplifies this well. Before 1903, Hausan farmers

rarely mono-cropped, but planted two or three differ-

ent crops in the same field. Each crop had different

requirements and tolerances to drought. This practice

minimized risk and guaranteed some food production

under almost any conditions. Water conservation

practices were also used as the need arose. If replanting

was required after an early drought, then the spacing

of plants was widened or fast-maturing cereals planted

in case the drought persisted. Hausan farmers also

planted crops suited to specific microenvironments.

Floodplains were used for rice and sorghum, inter-

fluves for tobacco or sorghum, and marginal land for

dry season irrigation and cultivation of vegetables.

Using these practices, the Hausan farmer could

respond immediately to any change in the rainfall

regime. Failing these measures, individuals could rely

upon traditional kinship ties to borrow food should