Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

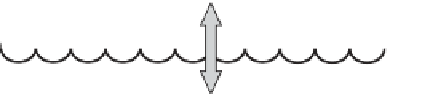

Figure 5.9

A schematic of the nitrogen

cycle. Each of the curved arrows

within the cycle represents a process

carried out by bacteria.

Atmosphere

Nitrogen

fixation

N

2

Denitrification

Ammonium

NH

4

Nitrate

NO

3

Nitrification

Nitrite

NO

2

Nitrification

invention of the Haber process,

2

nitrogen fixation by marine and terrestrial plants

was the dominant source of fixed inorganic nitrogen to the ocean (Galloway et al.,

2004

), and on very long timescales the nitrogen-fixing bacteria are thought to

govern the global pool of inorganic nitrogen available to the photosynthetic

autotrophs (Karl et al.,

2002

).

The reduction of nitrate back to nitrogen gas, N

2

, by bacteria is called

denitrification. This sink for nitrate generally takes place in regions depleted in

oxygen. It is of particular importance in estuaries, removing much of the nitrate

before it reaches the shelf seas, and also within sediments and the water column on

the shelf (Nixon et al.,

1996

; Hydes et al.,

2004

). You can think of the nitrogen cycle

as beginning with atmospheric N

2

being fixed by the diazotrophs, with different

species of bacteria then controlling the transfers of nitrogen from ammonium,

through to nitrite and nitrate, and eventually denitrification returning N

2

to the

atmosphere. This is summarised in the schematic illustration in

Fig. 5.9

. This bac-

teria-mediated cycle is independent of the rest of the marine primary production. The

autotrophic phytoplankton simply tap into the nitrogen cycle, temporarily diverting

some of the fixed nitrogen to aid their own growth.

One final point to note concerns the supply of silicate to the ocean. About two-

thirds of the silicate that enters the ocean is from the weathering of rocks on land and

subsequent transport down rivers into the coastal ocean, with another one-third from

volcanism and hydrothermal vents (Demaster,

1981

). The cycling of silicate within

the shelf seas, and the physical transports towards and across the shelf edge, are thus

important controls on the amount of silicate that reaches the open ocean.

2

The Haber process, developed by the German chemist Fritz Haber in early 20th century, is a vitally

important industrial method of fixing atmospheric nitrogen to ammonium in the production of

agricultural fertilisers. Today global anthropogenic fixation of nitrogen by the Haber process, along with

a smaller contribution from fossil fuel burning, fixes a similar amount of nitrogen as all marine and

terrestrial plant nitrogen fixers. See J. N. Galloway et al., (

2004

). Used to grow crops, this large amount

of fixed nitrogen eventually finds its way into rivers and the coastal ocean, leading to eutrophication.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search