Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

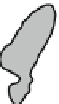

150° 35 '

150° 40'

150° 45'

150° 50'

34° 45'

Foys Swamp

Tsunami wave

crest

Tsunami

flood paths

Tsunami

backwash

34° 50'

Inland limit

of tsunami

flooding

Delta and

floodplain

Marsh or

swamp

Sand barrier

Tsunami

backwash

channel

Shoalhaven

River

34° 55'

Crookhaven

River

0

5 km

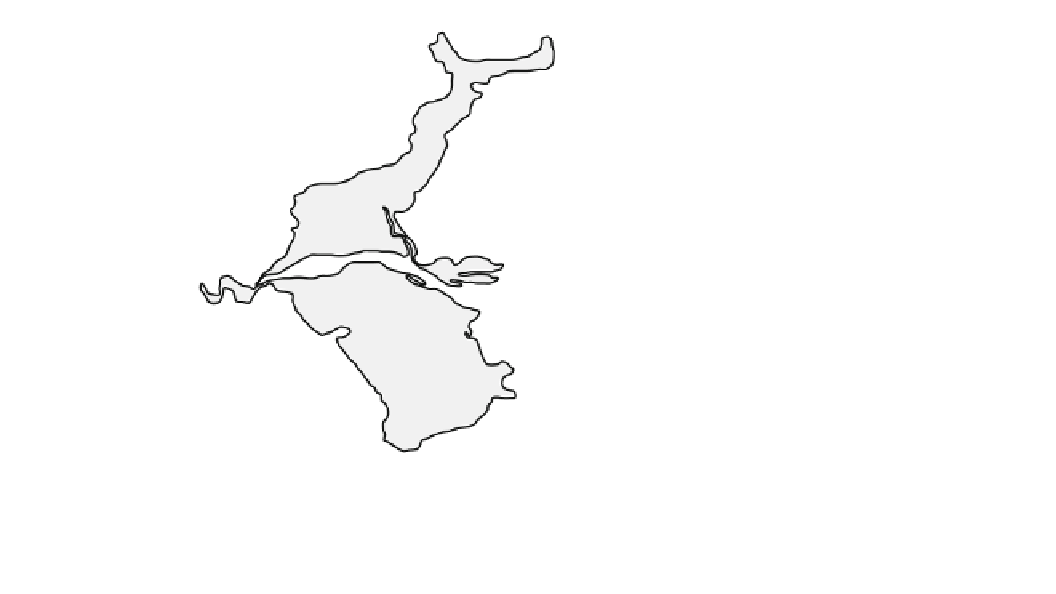

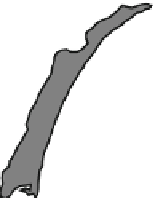

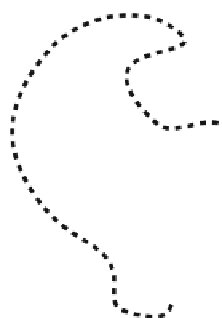

Fig. 4.4

Hypothesized tsunami overwashing of the Shoalhaven Delta,

New South Wales, and the meandering backwash channels draining

water off the Delta. A tsunami event 4730-5050 years ago—as

determined from shell buried within a tapering sand layer within the

delta—probably created these channels. The extent of this marine

layer is also marked. A younger tsunami event around AD

1410 ±60 years may also be implicated in the formation of the

backwash channels. Based on Young et al. (

1996b

)

southeast corner of the delta. The channels had a maximum

discharge of 500 m

3

s

-1

based upon the length of meanders.

The modern Shoalhaven River has a bankfull discharge of

3,000 m

3

s

-1

in flood. Many smaller streams were once

tidal, but the channels have since undergone infilling with a

reduction in their carrying capacity. The channels are

600 years old, coinciding with the regional age of a large

paleo-tsunami predating European settlement. This age was

obtained from oyster shells found on a raised pile of

imbricated boulders that were swept into the entrance of the

Crookhaven River as the tsunami approached from the

south. The wave then climbed onto the delta via this entrance

and the main channel of the Shoalhaven River (Fig.

4.4

).

The inferred direction of approach coincides with the

alignment of nearby boulders deposited by tsunami on cliffs

rising 16-33 m above sea level (Fig.

3.13

). The tsunami also

swept over a coastal sand barrier and onto the northern part

of the delta (Foys Swamp), depositing a layer of sand and

cobble 1.8 km inland of the modern shore. The small

meandering channels on the southern part of the delta were

created by southeast drainage of backwash from the deltaic

surface after the tsunami's passage northwards up the coast.

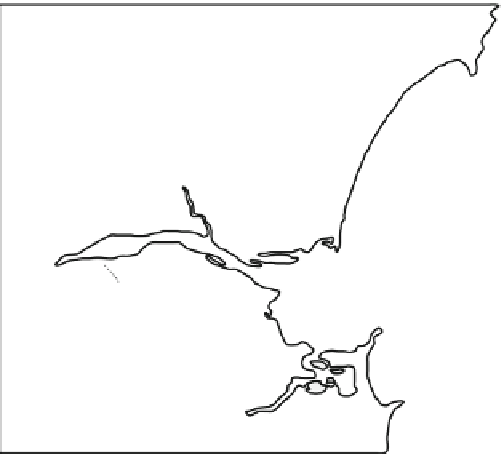

in Figs.

4.1

and

4.5

respectively. The two models can be

differentiated from each other by their degree of dissection.

Smooth, small-scale bedrock-sculptured landscapes are

restricted to headlands less than 7-8 m in height. Features

consist of S-forms and bedrock polishing, and rarely exceed

a meter in relief. Dump deposits and imbricated boulders

usually are present nearby. The S-forms are directional,

paralleling each other and the orientation of any imbricated

boulders. The landscape is dominated on the side of head-

lands facing the tsunami by fields of overlapping mus-

chelbrüche and sichelwannen grading into V-shaped

grooves as slopes steepen. Where vertical vortices develop,

broad potholes may form, but rarely with preserved central

bedrock plugs. Crude transverse troughs develop wherever

the slope levels off. At the crest of headlands, mus-

chelbrüche-like forms give way to elongated fluting. The

flutes taper downflow into undulating surfaces on the lee

slope. Sinuous cavitation marks and drill holes develop on

this gentler surface wherever flow accelerates because of

steepening or flow impingement against the bed. On some

surfaces, a zone of fluting and cavitation marks may reap-

pear towards the bottom of the lee slope because of flow

acceleration. Cavettos or drill holes develop wherever ver-

tical faces are present. While cavettos are restricted to

surfaces

4.4.3

Rocky Coasts

paralleling

the

flow,

cavitation

marks

are

ubiquitous.

Irregular, large-scale, bedrock-sculptured landscapes are

most likely created by large tsunami generated by sub-

marine landslides and asteroid impacts with the ocean. The

There are two distinct models of sculptured landscape for

rocky coasts: smooth, small-scale and irregular, large-scale

(Bryant and Young

1996

). These are shown schematically