Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

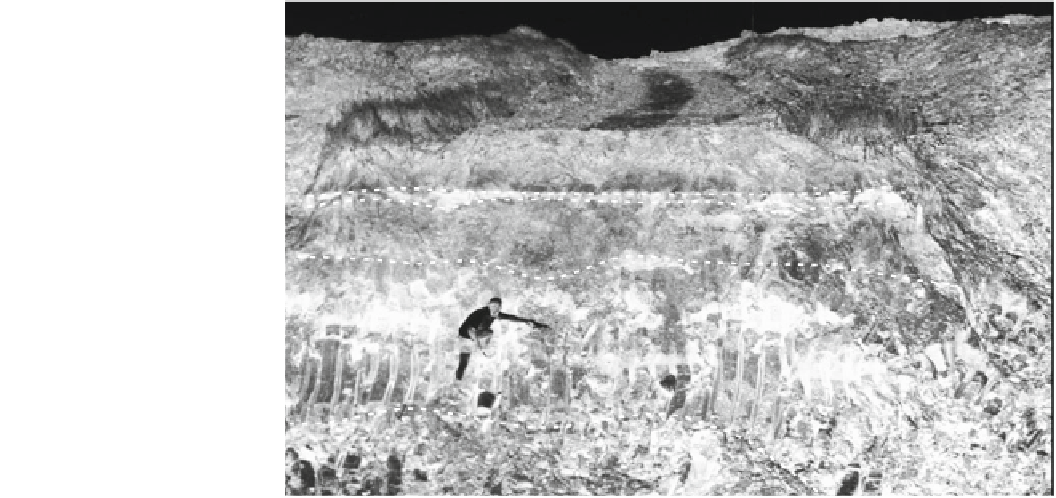

Fig. 4.2

Section through the

barrier beach at Bellambi, New

South Wales, Australia: a modern

dune, b Holocene barrier sand

dated using thermoluminescence

(TL) at 7,400 BP, c clay unit,

d tsunami sand TL—dated at

25,000 BP, e Holocene estuarine

clay radiocarbon dated at 5,100

BP, and f Pleistocene estuarine

clay TL—dated at more than

45000 years in age. The TL date

of the tsunami sand indicates that

the sands are anomalous. The

Holocene ages overlap

a

b

c

d

e

f

4.4.1

Sandy Barrier Coasts

the Papua New Guinea Tsunami of July 17, 1998 (Kawata

et al.

1999

). The emplacement of a sand deposit overtop

lagoonal sediments on a coastline with stable sea level may

signify the presence of recent tsunami where historical

evidence for such events is lacking. Pre-existing tidal inlets

are preferred conduits for tsunami. Sediment-laden tsunami

may deposit large, coherent deltas at these locations, and

these may be mistaken for flood tidal deltas (Minoura and

Nakaya

1991

; Andrade

1992

). These features may be raised

above present sea level or form shallow shoals inside inlets.

Because the sediment was deposited rapidly, these deltas

may end abruptly landward in lagoons and estuaries,

forming sediment thresholds that are stable under present-

day tidal flow regimes. Channels through the lagoon can

also be scoured by tsunami, with sediment being deposited

on the landward side of lagoons as splays.

If the volume of sand transported by a tsunami is large,

then a raised backbarrier platform may form from coa-

lescing overwash fans or smaller lagoons may be com-

pletely infilled. The height of either the backbarrier

platform or infilled lagoon may lie several meters above

existing sea level. These raised lagoons may be misinter-

preted as evidence for a higher sea level. If these surfaces

are not covered by seawater or quickly vegetated, they may

be subject to wind deflation, with the formation of small

hummocky dunes. Under extreme conditions, tsunami

waves may cross a lagoon, overwash the landward shore-

line, and deposit marine sediment as chenier ridges. Such

ridges ring the landward sides of lagoons in New South

Wales. Finally, along ria coastlines, estuaries may be in-

filled with marine sediment for considerable distances up-

river. High-velocity flood and backwash flows under large

tsunami may form pool and riffle topography. This process

Large sections of the world's sandy coastline are charac-

terized by barriers either welded to the coastline or sepa-

rated from it by shallow lagoons. The origin of these

barriers has been attributed to shoreward movement of

sediment across the shelf by wind-generated waves, con-

comitantly with the Holocene rise of sea level (Komar

1998

). Lagoons form where the rate of migration of sand

deposits lags the rate at which the rising sea drowns land.

This theory of barrier formation ignores the role of tsunami

as a possible mechanism, not only for shifting barriers

landward, but also for building them up vertically. For

example, at Bellambi along the New South Wales coast of

Australia, tsunami-deposited sands make up 20-90 % of the

vertical accretion of a barrier beach that stands 3-4 m above

present sea level (Fig.

4.2

). This beach will be described in

more detail subsequently (Young et al.

1995

).

Tsunami in shallow water are constructional waves with

the potential to carry large amounts of sand and coarse-

grained sediment shoreward. Large aeolian dunes that may

develop on stable barriers do not necessary impede tsunami

(Minoura and Nakaya

1991

; Andrade

1992

). Instead, tsu-

nami can overwash such forms, reducing the height of the

dunes, depositing sediment in dune hollows, and spreading

sand as a thin sheet across backing lagoons (Fig.

4.3

). On

the other hand, storm waves tend to surge through low-lying

gaps in dune fields, sporadically depositing lobate washover

fans in lagoons (Bryant and McCann

1973

). Rarely will

these fans penetrate far into a lagoon or coalesce. The

seaward part of the barrier can also be translated rapidly

landward tens of meters by the passage of a tsunami. This

occurred along the barrier fronting Sissano lagoon during