Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

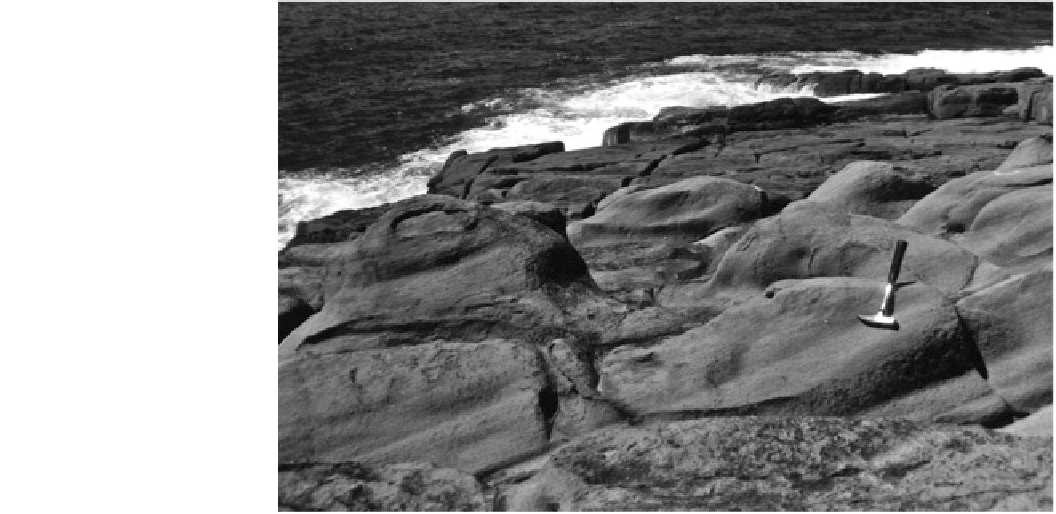

Fig. 3.20

Flutes developed on

the crest of a ramp 14 m above

sea level at Tura Point, New

South Wales Australia. The

depressions on the sides of the

flutes are cavettos. Flow from left

to right

downstream. V-shaped grooves have no sub-glacial equiv-

alent and can span a large range of sizes. For instance, at

Bass Point, New South Wales, V-shaped grooves over 30 m

wide

contemporary wave attack is one of the best indicators of

high-velocity tsunami flow over a bedrock surface.

On flat surfaces, longitudinal vortices give way to ver-

tical ones that can form hummocky topography and pot-

holes (Fig.

3.17

). Potholes are one of the best features

replicated at different scales by high-velocity tsunami flow.

While large-scale forms can be up to 70 m in diameter,

smaller features have dimensions of 4-5 m (Alexander

1932

; Baker

1981

; Kor et al.

1991

). The smaller potholes

also tend to be broader, with a relief of less than 1 m. The

smaller forms can exhibit a central plug, but this is rare

(Fig.

3.21

). Instead, the potholes tend to develop as flat-

floored, steep-walled rectangular depressions, usually

within the zone of greatest turbulence. While bedrock

jointing may control this shape, the potholes' origin as

bedrock-sculptured features is unmistakable because the

inner walls are inevitably undercut or imprinted with

cavettos. In places where vortices have eroded the con-

necting walls between potholes, a chaotic landscape of

jutting bedrock with a relief of 1-2 m can be produced. This

morphology—termed hummocky topography—forms

where flow is unconstrained and turbulence is greatest

(Bryant and Young

1996

). These areas occur where high-

velocity water flow has changed direction suddenly, usually

at the base of steep slopes or the seaward crest of headlands.

The steep-sided, rounded, deep potholes found isolated on

intertidal rock platforms, and attributed to mechanical

abrasion under normal ocean wave action, could be cata-

strophically sculptured forms. Intriguingly, many of these

latter features also evince undercutting and cavettos along

their walls.

and

spanning

approximately

10 m

in

relief

have

developed on slopes of more than 20.

The term flute describes long linear forms that develop

under unidirectional, high-velocity flow in the coastal

environment (Bryant and Young

1996

). These are notice-

able for their protrusion above, rather than their cutting

below, bedrock surfaces (Figs.

3.19

and

3.20

). In a few

instances, flutes taper downstream and are similar in shape

to rock drumlins and rattails described for catastrophic flow

in sub-glacial environments. In all cases, the steeper end

faces the tsunami, while the spine is aligned parallel to the

direction of tsunami flow. Flutes span a range of sizes,

increasing in length to 30-50 m as slope decreases. How-

ever, their relief rarely exceeds 1-2 m. Larger features are

called rock drumlins. The boulder trails at Tuross Head,

mentioned above, are constrained by flutes. Fluted topog-

raphy always appears on the seaward crest of rocky prom-

ontories where velocities are highest. Flutes often have

faceting or cavettos superimposed on their flanks. Faceting

consists of chiseled depressions with sharp intervening

ridges (Maxson

1940

). They represent either the impinge-

ment of vortices instantaneously upon a bedrock surface or

hydraulic hammering of rock surfaces by high-velocity

impacts. Cavettos are curvilinear grooves eroded into steep

or vertical faces by erosive vortices (Kor et al.

1991

). While

cavetto-like features can form due to chemical weathering

in the coastal zone, especially in limestones, their presence

on resistant bedrock at higher elevations above the zone of