Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

Fig. 10.4

People fleeing the

third and highest tsunami wave

that flooded the seaside

commercial area of Hilo, Hawaii,

following the Alaskan earthquake

of April 1, 1946. Photograph

courtesy of the U.S. Geological

Survey. Source Catalogue of

Disasters #B46D01-352

Turbulent

jetting

through

trees

Wave bore

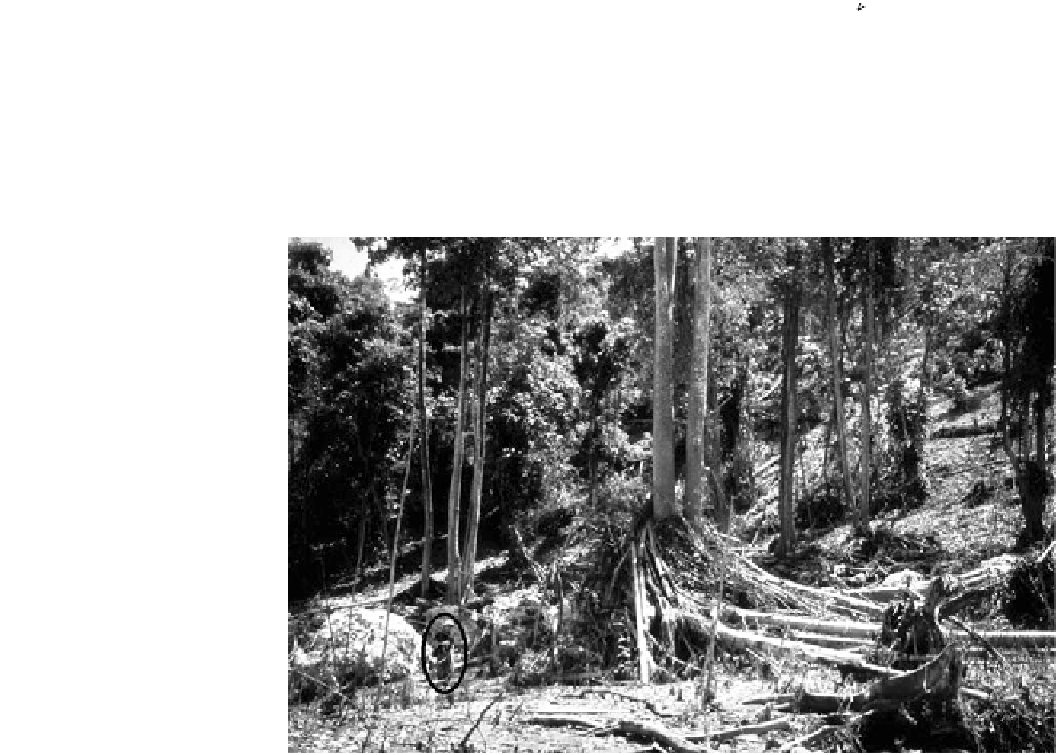

Fig. 10.5

Coral boulders

deposited in the forest at

Riang-Kroko, Flores, Indonesia

following the tsunami of

December 12, 1992. Note the

person circled for scale and the

abrupt termination of debris

upslope. Photo Credit Harry Yeh,

University of Washington.

Source NOAA National

Geophysical Data Center

and when they get into harbors, especially ones where the

width of the entrance is small compared to the length of the

harbor's foreshores, they become trapped and cannot escape

back out to sea easily. Inside a harbor or bay, long waves

such as tsunami tend to travel back and forth for hours

dissipating their energy, not across the deeper portions but

against the infrastructure built on the shoreline. Rapid

changes in sea level and dangerous currents can be gener-

ated. Ria coastlines, such as those along the coast of Japan

or southeastern Australia are ideal environments in which

these effects can develop. Boats in harbors are particularly

vulnerable and should put out to sea and deeper water fol-

lowing any tsunami warning.

Fifth, treat rivers exactly like long harbors. When a

tsunami gets into a tidal river or estuary where water depths

can still be tens of meters deep, the wave can travel easily

up the river to the tidal limits or beyond. Along some coasts,

tide limits may be tens of kilometers upriver, and residents

living along the riverbanks may be very unaware that a

threat from tsunami exists. If the river is deep and allows

the penetration of the wave upstream, the height of a long

wave can rapidly amplify where depth shoals or the river

narrows. At these locations, water can spill over levees and

banks, flooding any low-lying topography. In its publication

Tsunami! The Great Waves, the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (

2012

) likewise warns, ''Stay

away from rivers and streams that lead to the ocean as you

would stay away from the beach and ocean if there is a

tsunami.''

Sixth, tsunami have an affinity for headlands that stick out

into the ocean, mainly because wave energy is concentrated

here by wave refraction. Storm waves can increase in

amplitude on headlands two- or threefold relative to an

adjacent embayed beach. Tsunami are no different.