Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

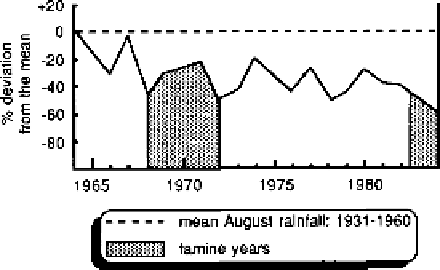

Figure 3.9

August rainfall in the Sahel: 1964-84

unknown medical services—such as vaccination

programmes—and led to improvements in child

nutrition and sanitation. Together these helped

to lower the death rate, and, with the birth rate

remaining high, populations grew rapidly,

doubling between 1950 and 1980 (Crawford

1985). The population of the Sahel grew at a

rate of 1 per cent per annum during the 1920s,

but by the time of the drought in the late 1960s

the rate was as high as 3 per cent (Ware 1977).

Similar values have been calculated for the

eastern part of the dry belt in Somalia (Swift

1977) and Ethiopia (Mackenzie 1987b). Initially,

even such a high rate of growth produced no

serious problems, since in the late 1950s and early

1960s a period of heavier more reliable rainfall

produced more fodder, and allowed more animals

to be kept. Crop yields increased also in the arable

areas. Other changes, with potentially serious

consequences, were taking place at the same time,

however. In the southern areas of the Sahel, basic

subsistence farming was increasingly replaced by

the cash-cropping of such commodities as

peanuts and cotton. The way of life of the

nomads had already been changed by the

establishment of political boundaries in the

nineteenth century, and the introduction of cash-

cropping further restricted their ability to move

as the seasons dictated. Commercialization had

been introduced into the nomadic community

also, and in some areas market influences

encouraged the maintenance of herds larger than

the carrying capacity of the land. This was made

possible, to some extent by the drilling or digging

of new wells, but as Ware (1977) has pointed

out, the provision of additional water without a

parallel provision of additional pasture only

served to aggravate ecological problems. All of

these changes were seen as improvements when

they were introduced, and from a socio-economic

point of view they undoubtedly were.

Ecologically, however, they were suspect, and,

in combination with the dry years of the 1960s,

1970s and 1980s, they contributed to disaster.

The grass and other forage dried out during

the drought, reducing the fodder available for

the animals. The larger herds—which had

Source:

After Cross (1985a)

disease and death. In contrast, good years are

those in which the ITCZ, with its accompanying

rain, moves farther north than normal, or remains

at its poleward limits for a few extra days or

even weeks.

In the past, this variability was very much part

of the way of life of the drought-prone areas in

sub-Saharan Africa. The drought of 1968 to 1973

in the Sahel was the third major dry spell to hit

the area this century, and although the years

following 1973 were wetter, by 1980 drier

conditions had returned (see Figure 3.9). By 1985

parts of the region were again experiencing fully

fledged drought (Cross 1985a). A return to

average rainfall in 1988 provided some respite,

but it was short-lived, and in 1990 conditions

again equalled those during the devastating

droughts of 1972 and 1973 (Pearce 1991b).

Much as the population must have suffered in

the past, there was little they could do about it,

and few on the outside showed much concern.

Like all primitive nomadic populations, the

inhabitants of the Sahel increased in good years

and decreased in bad, as a result of the checks

and balances built into the environment.

That situation has changed somewhat in

recent years. The introduction of new scientific

medicine, limited though it may have been by

Western standards, brought with it previously