Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

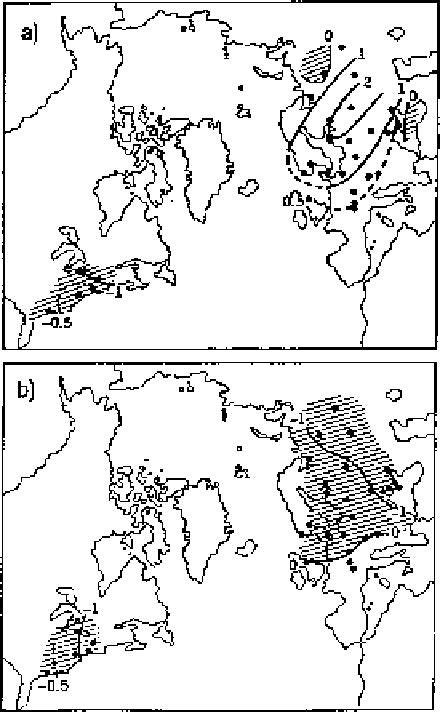

Figure 5.6

Mean anomalies of surface air temperature

(°C) for the period 2 to 3 years after volcanic

eruptions with volcanic explosivity power

approximately equal

to the Krakatoa eruption, (a) Winter (b) Summer.

Points show the stations used. Dashed regions depict n

egative anomalies

produced a similar pattern, and Groisman

suggests that the unusually mild winter of 1991-

92 in central Russia was an indication of a

positive anomaly associated with Mount

Pinatubo. The warming is seen as a result of the

greater frequency of westerly winds over Europe,

which owe their development to an increase in

zonal temperature gradients following the general

global cooling associated with major volcanic

eruptions.

Volcanoes have the ability to contribute to

changes in weather and climate at a variety of

temporal and spatial scales. At a time when the

human input into global environmental change

is being emphasized, it is important not to ignore

the contribution of physical processes, such as

volcanic activity, which have the ability to

augment or diminish the effects of the

anthropogenic disruption of the earth/

atmosphere system.

THE HUMAN CONTRIBUTION TO

ATMOSPHERIC TURBIDITY

The volume of particulate matter produced by

human activities cannot match the quantities

emitted naturally (see Figure 5.7). Estimates of

the human contribution to total global particulate

production vary from as low as 10 per cent (Bach

1979) to more than 15 per cent (Lockwood 1979)

with values tending to vary according to the size-

fractions included in the estimate. Human

activities may provide as much as 22 per cent of

the particulate matter finer than 5 µm, for

example (Peterson and Junge 1971). It might be

expected that the human contribution to

atmospheric turbidity would come mainly from

industrial activity in the developed nations of the

northern hemisphere, and that was undoubtedly

the case in the past, but data from some

industrialized nations indicate that emissions of

particulate matter declined in the 1980s (see

Figure 5.8). There is also some evidence that the

burning of tropical grasslands is an important

source of aerosols (Bach 1976), and although

specific volumes are difficult to estimate, smoke

and soot released during the burning of tropical

Source:

From Groisman (1992)

Groisman (1992) has compared temperature

records in Europe and the northeastern United

States with major volcanic eruptions between

1815 and 1963. The results show that in western

Europe, and as far east as central Russia and

Ukraine, statistically significant positive

temperature anomalies occur in the winter

months some 2 to 3 years after an eruption the

size of Krakatoa (see Figure 5.6). The analysis of

data following the eruption of El Chichón