Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

not coincide with the greatest cumulative DVI.

Thus, although increased volcanic activity and

the associated dust veils can be linked to

deterioration between 1430 and 1850, it is likely

that volcanic dust was only one of a number of

factors which contributed to the development of

the Little Ice Age at that time.

Major volcanic episodes in modern times have

usually been accompanied by prognostications

on their impact on weather and climate, although

it is not always possible to establish the existence

of any cause and effect relationship. The Agung

eruption produced the second largest DVI this

century, but its impact on temperatures was less

than expected, perhaps because the dust fell out

of the atmosphere quite rapidly (Lamb 1970). It

is estimated that it depressed the mean

temperature of the northern hemisphere by a few

tenths of a degree Celcius for a year or two

(Burroughs 1981), but such a value is well within

the normal range of annual temperature

variation. The spectacular eruption of Mt St

Helens in 1980—enhanced in the popular

imagination by intense media coverage—

promoted the expectation that it would have a

significant effect on climate, and it was blamed

for the poor summer of 1980 in Britain. In

comparison to other major eruptions in the past,

however, Mt St Helens was relatively insignificant

in climatological terms. It may have produced a

cooling of a few hundredths of a degree Celcius

in the northern hemisphere, where its effects

would have been greatest (Burroughs 1981). The

eruption of El Chichón in Mexico in 1982

produced the densest aerosol cloud since

Krakatoa, nearly a century earlier. Within a year

it had caused global temperatures to decline by

at least 0.2°C and perhaps as much as 0.5°C

(Rampino and Self 1984). However, the cooling

produced by El Chichón may have been offset

by as much as 0.2°C as the result of an El Niño

event which closely followed the eruption, and

effectively prevented cooling in the southern

hemisphere (Dutton and Christy 1992) (see

Figure 5.5). Past experience suggested that the

eruption of Mount Pinatubo would also lead to

lower temperatures. It was blamed for the cool

summer of 1992 in eastern North America, and

by September of that year it was linked with

reductions in global and northern hemisphere

temperatures of 0.5°C and 0.7°C respectively

(Dutton and Christy 1992). Estimates by

modellers studying world climatic change

indicate that such cooling would be sufficient to

reverse—at least temporarily—the global

warming trends characteristic of the 1980s

(Hansen

et al.

1992).

Although volcanic activity is most commonly

associated with cooling, there is some evidence

that it may also cause short-term, local warming.

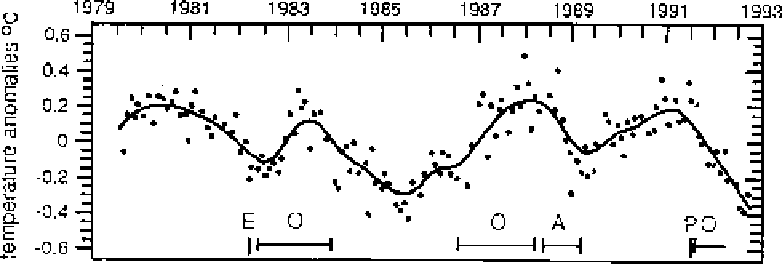

Figure 5.5

Monthly mean global temperature anomalies obtained using microwave sounding units (MSU).

The events marked are: A—La Niña; O—El Niño; E—El Chichón; P—Pinatubo

Source:

After Dutton and Christy (1992)