Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

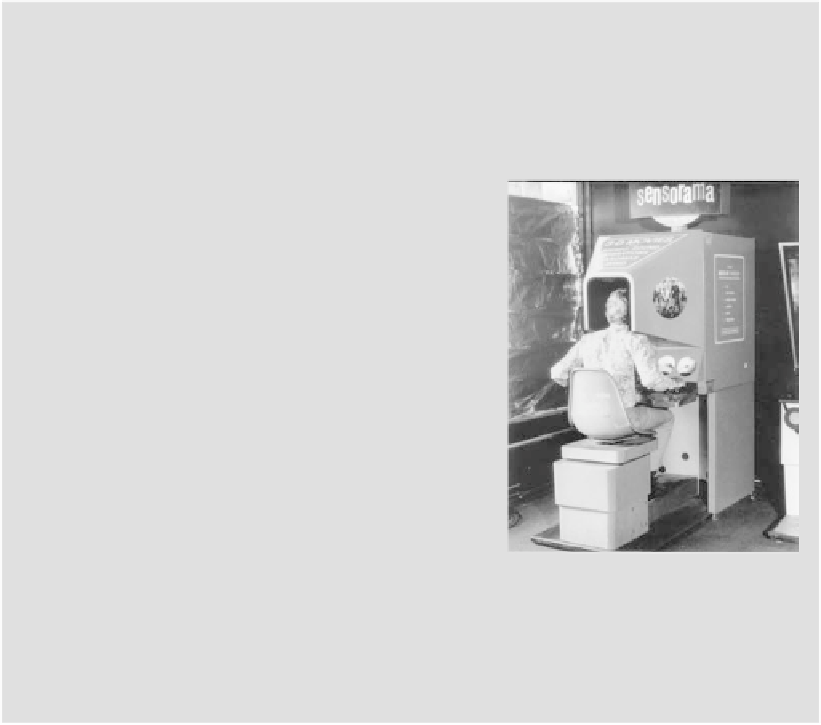

Morton Heilig: a Genius and a Member of the Crash Dummy Club

Morton Heilig is regarded as a pioneer in Virtual Reality. He invented the Sensorama Simulator (also

called the Sensorama Machine) in 1957 as part of a larger plan to reinvent cinema, called Experi-

ence Theatre. The machine allowed interactors to view a stereoscopic video scene augmented with

vibrating handlebars and a moving seat, wind effects,

and scents. He created fi ve experiences for the machine

including a bicycle ride, a ride on a dune buggy, a hel-

icopter ride over Century City, and a motorcycle ride

through New York. The most amazing thing about Sen-

sorama was that it was entirely mechanical; nowadays we

think of VR as a computational system. I think it's also in-

teresting that he called the genre “Experience Theatre”—

a sort of blend between cinema, theatre, and arcade ride.

Ultimately, Heilig couldn't get funded to build the rest of

his dream. He died in 1996.

Heilig became a member of what I call the Crash

Dummy club, to which I also belong. That's folks who

had ideas to make things before they were economi-

cally feasible—things that were ahead of their time.

Our work with VR at Telepresence Research (with Scott

Fisher, Michael Naimark, Steve Saunders, Mark Bolas, Scott Foster, and Rachel Strickland) as well as

the Placeholder VR project in Banff qualifi ed us for the Crash Dummy club.

Being a Crash Dummy is an uncomfortable but fi ne, wild ride.

Sensorama

One probably temporary difference between drama and human-

computer interaction is the senses that are addressed in the enactment.

9

Tra-

ditionally, plays are available only to the eyes and ears; we cannot touch,

9. Aristotle defi ned the enactment in terms of the audience rather than the actors. Although

actors employ movement (kinesthetics) in their performance of the characters, that movement

is perceived visually; the audience has no direct kinesthetic experience. Likewise, although

things may move about on a computer screen, a human user may or may not be having a kin-

esthetic experience. In biology, the relatively recent discovery of mirror neurons in the brains

of humans and some higher primates challenge this view. Science has shown that, when ob-

serving another individual doing something, “mirror neurons” in the observer's brain respond

as if the observer were taking the same action. This may go a long way toward defi ning at least

some of the physical basis for empathy (see Keysers 2011).