Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

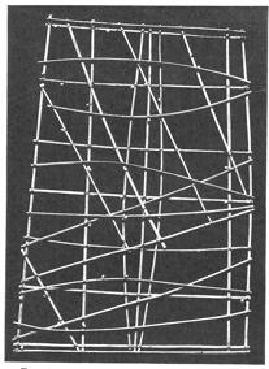

charts of ocean swells that were used by Marshallese canoe navigators for centuries. It's

remarkable that these people could pilot from atoll to atoll on the open sea based solely on

wave patterns, but it's also interesting that we haven't found a single map of the Pacific

made by any of the

hundreds of other

island cultures. Some people, apparently, get by just

fine without written maps.

“Mapmaking might be innate in the same way that reading is innate,” Uttal suggests.

“And that's a very complex thing: reading text is obviously

not

innate, but the language

upon which it is based is.”

Sowhichpartsofcartographymightactuallybeasinstinctiveaslanguageandnot(fairly

recent) cultural innovations? Well, we all make mental maps, models of our surroundings

that we store in our heads. Calling such a construct a “map” might be misleading, though,

since our mental maps don't have much in common with paper ones. They're not static;

they're not one-to-one replicas of actual topography; they don't rely on symbols and in

some cases may not even involve landmarks. (You also can't refold them badly and shove

thembackintoyourglovecompartment.)WhenIaskmyfriendNephiThompson,whohas

the best sense of direction of anyone I know, to describe how he sees his mental map in his

mind's eye, he says, “It's like a first-person shooter game, an over-the-shoulder perspect-

ive. It's not a bird's-eye view.”

A Micronesian road map: the tiny seashells are islands and the bamboo strands currents

Humanshavebeenmakingmentalmapsmillionsofyearslongerthanthey'vebeenmak-

ing written ones, of course. The very first time some hairy hominid ever decided to alter

his hunting route to avoid an obstacle or a predator, he was drawing a mental map. In fact,