Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

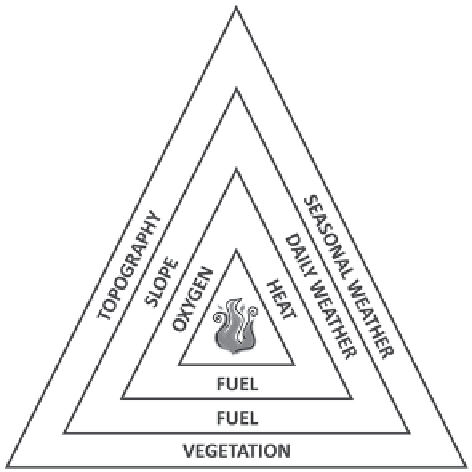

Fig. 2.1

A new variation on

the traditional fire triangle

often used to teach fire sci-

ence to managers. The

inner

triangle

refers to combustion

at the flame level, the

middle

triangle

refers to fire spread

at a stand level, and the

outside triangle

refers to fire

growth at the landscape level

more oxygen than can be supplied by the atmosphere, thereby governing burning

rates. And last, there is fuel. As Van Wagner (

1983

) mentions, the fuel must be the

appropriate size and arrangement to facilitate fire spread and it must be dry enough

for combustion (i.e., low moisture content). Unfortunately, the inner fire triangle in

Fig.

2.1

really only works at very small scales; perhaps the scale of the flame, which

may be useful for firefighters but somewhat ineffectual for the diverse and complex

issues facing a wildland fuel manager. Therefore, many have added additional fire

triangles to represent the scaling of combustion to a fire event (Fig.

2.1

; Alexander

2014

).

However, to fully understand fuels, it is important to recognize that the process

of combustion scales from the flame to burning period to fire event over various

time and space scales (Fig.

2.1

). A more comprehensive representation of the fire

triangle is detailed by Moritz et al. (

2005

; Fig.

2.2

) where fire moves across an area

and interacts with topography (slope, aspect), weather (temperature, humidity), and

the fuel complex. At coarser scales, the fuel properties important to fire spread are

governed more by the distribution of fuels across the landscape or contagion (con-

tinuity of a fuelbed). The landscape-level spatial scale of fire spread best describes

the operational management of fuels and is probably the most appropriate for de-

signing fuel treatments (Agee and Skinner

2005

). However, some large fires can

burn entire landscapes over the course of weeks, and as more fires burn the same

landscape over hundreds of years, these fires interact with previous fires, climate

(drought, warming), ignition patterns (lightning, humans), and vegetation to create

a

fire regime

(Chap. 6). In Fig.

2.2

, fuels are represented by vegetation to signify

that fuel conditions change over time and this change is mediated by vegetation

development processes (regeneration, growth, mortality) and succession (species

Search WWH ::

Custom Search