Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

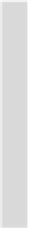

Fig. 2

Proportion of length of

shoreline according to the

different coastal facies (SDLAO,

UEMOA-IUCN

2011

). Note the

high proportion of mangrove

coasts, also related to the highly

fractal dimension that

characterises the shoreline in

these milieus

extend their capacity, or will do so in the near future. The

increasing penetration of the private sector in the manage-

ment and even building of ports (for ore ports) should act as

an incentive to the States to be vigilant in taking into

account the environmental and coastal impacts of these new

facilities.

• Relict of sandstone or hardpan spared by erosion (sand-

stone on the Senegalese Petite Côte, the Bijagos and

around the periphery of Accra).

• Granites and metamorphic rocks presents on all of

Liberia, Western Côte d'Ivoire and the central part of the

coast of Ghana.

The remainder of the coast line is composed of:

Unstable and/or very dynamic coasts

• Sand banks, estuaries, river mouths, spits and islets by

nature also very unstable and dynamic (12 %).

• Mangroves, continuously evolving (48 %).

• Sandy formations of lidos, thin sandy rim between a

lagoon

A Fragile, Dynamic Coastline

On the coasts constituted of sedimentary accumulation, which

are by far the most common in West Africa, the mobility of the

shoreline largely depends on the local balance of supply and

removal in the sediment budget. Removal operates under the

action of natural agents (coastal drift, ocean waves, wind, etc.),

which are also partly responsible for sediment supply. Removal

may also be the result of human activity, either directly

(extraction from the beaches of raw materials for building

activities, for instance), or indirectly (the creation of surfaces

that reflect wave energy or installations that disrupt the oper-

ation and the exchanges between the different sediment com-

partments of the beaches or that disturb the coastal drift parallel

to the shore). The dams situated on the catchment areas also

constitute traps for continental sediment which no longer

reaches the coast, increasing the sediment deficit, particularly at

the level of the estuaries and mouths of rivers.

and

the

sea

shore,

also

unstable

and

highly

changing (7 %).

Less dynamic coasts, but still subject to natural episodes

of erosion and accretion outside of human intervention.

• More or less straight sandy coasts, fashioned by the

coastal drift currents, relatively stable but subject to

cyclical phases of erosion and accretion, also very sen-

sitive to nay disruptions of the coastal drift (16 %).

• Stepped coasts or headlands and coves, where the coves

are compartments more or less separated by rock out-

crops or less soft. Their stability strongly depends on the

orientation in relation to the ocean waves and currents

(14 %). The sediment stocks here are often very limited

(Fig.

2

).

Of the estimated less than 6,000 km of coastline (at a scale

of 1:75,000) from Mauritania to Benin, rocky coasts repre-

sent fewer than 3 % of the coast line. These coasts are made

of rock that is often altered and fractured, subject to land-

slides and erosion. There are, however, a few rock outcrops

that structure this coast in headlands that are less soft but

often fractured and fragile, and especially few in number:

• Basalts and other rocky formations on the Cape Verde

Peninsula (Senegal).

• Rock outcrops at Cap Verga and the Conakry peninsula

(Guinea).

• Breakwater at Freetown (Sierra Leone).

The whole of this coastal system is first of all

conditioned by the sediment legacies dating from the

last transgressions and remobilised by the morpho-

genic agents (currents, winds and ocean waves).

Continental fluxes, whether aeolian or fluviatile, only

partially contribute to maintaining the legacy stocks.

This is nonetheless a hypothesis which has not yet

been confirmed.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search