Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

cooperative discussion to occur between us all while making decisions as a group

about how to progress, whom to save, and whom to leave behind. We became

co-constructors of our narrative: this most dramatically manifested when our

game literally depended on the results of one dice roll, which sadly, we lost.

he Complete Trilogy

also functions as an example of convergence culture,

especially as it relates to audience empowerment. Although the aesthetics of

the game follow Peter Jackson's ilmic version of the story, the actual game play

difers signiicantly. In

he Complete Trilogy,

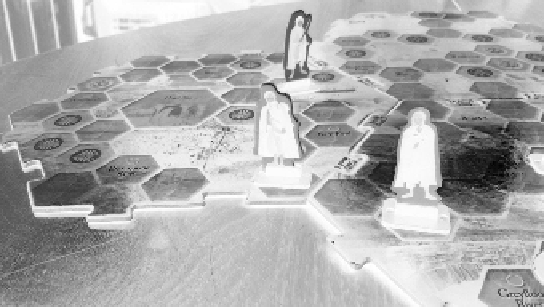

the game board is a giant map of

Middle-earth. he game board itself is constructed from twelve interlocking

pieces, which do not allow structured breaks as in Knizia's version (see Figure 2.3

for one of those pieces). While it is an enjoyable experience to join the pieces

together—and the fact they “it” with the game version of Jackson's

he Hobbit

series of ilms as well makes them particularly useful as paratextual tools—they

ultimately do not shit or move and simulate a traditional immobile game board.

he luidity of the game is uninterrupted by breaks in the action, as characters

might be constantly moving around the static board.

39

In one game we created a storyline wherein the Nazgûl inhabited the Shire,

near Hobbiton, and destroyed all the escaping Hobbits. Aragon and Boromir

were constantly getting into scrapes, and Frodo was antisocial and only wanted

to mope. As Gray describes, citing Ellen Seiter, toys can become “generative of

their

own

meanings,” and as “'mass-media goods, these kind of toys actually

facilitate group, co-operative play, by encouraging children to make up stories

with shared codes and narratives.”

40

he stories that our group made up during

our

he Complete Trilogy

game play diverged greatly from those of Jackson's

Figure 2.3

A piece of Middle-earth. Photo by the author.

39

Search WWH ::

Custom Search