Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

themselves pressed together to one side. We have more to say about this

particular situation in

Section 11.8.

We can learn a lot about acceleration just by asking ourselves what sort

of units we should use to measure it. For velocity, we used the generic units

of L/T, unit length per unit time. Velocity is a rate of change of position

(L) per unit time (T), and so this makes sense. Acceleration is the rate of

change of velocity per unit time, and so it must be expressed in terms of

“unit velocity per unit time.” In fact, the units used to measure velocity

are L/T

2

. If you are disturbed by the idea of “time squared,” think of it

instead as (L/T)/T, which makes more explicit the fact that it is a unit of

velocity (L/T) per unit time.

For example, an object in free fall near Earth's surface accelerates at a

rate of about 32 ft/s

2

, or 9.8 m/s

2

. Let's say that you are dangling a metal

bearing off the side of Willis Tower.

27

You drop the bearing, and it begins

accelerating, adding 9.8 m/s to its downward velocity each second. (We are

ignoring wind resistance.) After, say, 2.4 seconds, its velocity will be

s

2

= 76.8

ft

ft

2.4 s × 32

s

.

More generally, the velocity at an arbitrary time t of an object under con-

stant acceleration is given by the simple linear formula

v(t) = v

0

+ at,

(11.13)

where v

0

is the initial velocity at time t = 0, and a is the constant ac-

celeration. We study the motion of objects in free fall in more detail in

Section 11.6,

but first, let's look at a graphical representation of accelera-

tion.

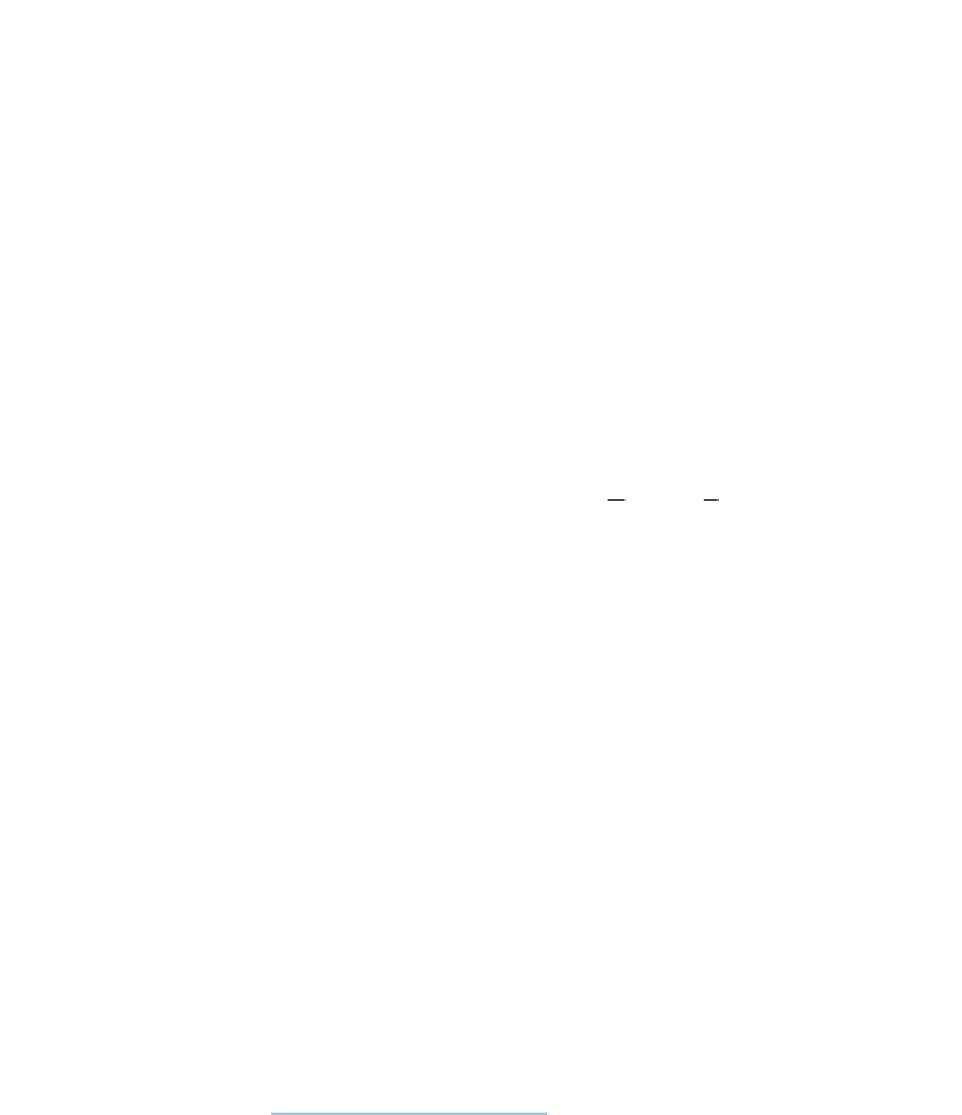

Figure 11.9

shows plots of a position function and the corresponding

velocity and acceleration functions.

You should study Figure 11.9 until it makes sense to you. In particular,

here are some noteworthy observations:

•

Where the acceleration is zero, the velocity is constant and the posi-

tion is a straight (but possibly sloped) line.

•

Where the acceleration is positive, the position graph is curved like

.

The most interesting example occurs on the right side of the graphs.

Notice that at the time when the acceleration graph crosses a = 0,

the velocity curve reaches its apex, and the position curve switches

from

, and where it is negative, the position graph is curved like

to

.

27

The building that everybody still calls the Sears Tower.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search