Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

The channel between boredom and frustration is an ideal path, like a perfect model that many

games strive for. In a game with perfect flow, the player would push and be pushed back but

would be so engaged in what's going on that it would all feel seamless, natural. Some games

are good at finding this channel—even if they don't start there at the beginning of a player's

experience!

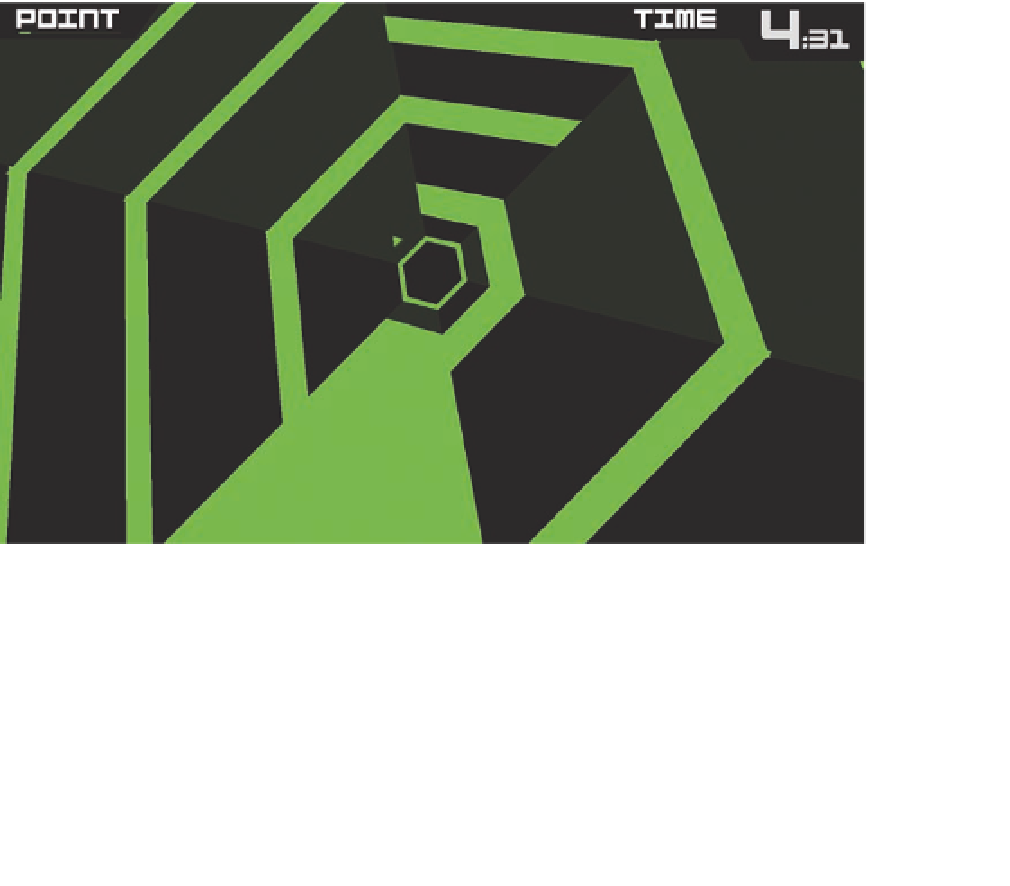

Super Hexagon

(2012) by Terry Cavanagh is an interesting example. To play, you simply use the

verbs “rotate clockwise” and “rotate counterclockwise” to keep the arrow you control from col-

liding with a series of walls closing in from the outside of the screen (see Figure

). The player

has to rotate the triangle to go through the gaps. At the beginning, this is an incredibly difficult

task, and a player is likely to die by colliding with a wall almost immediately, making game ses-

sions last less than ten seconds. At first, this seems like a clear violation of the “perfect model”

6.3

of flow, but

Super Hexagon

uses a simple enough system that it doesn't need to start off slow

and easy. The player learns what to do by colliding with walls, over and over again. Because

these early sessions are so short, it's easy for the player to jump in again, grasp the patterns of

walls that close in on her, and hone her reflexes.

Figure 6.3

Super Hexagon

dares to start off super-challenging.

Before long, many players will improve—and notice that they've improved, since their game

sessions (and “longest time” records) will be getting longer. This kind of motivating feedback is

essential for flow, but it's worth noting that

Super Hexagon

doesn't start off at the bottom-left