Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

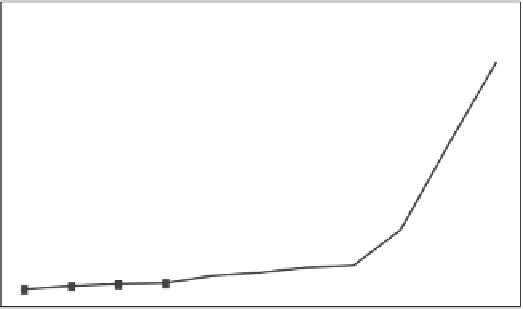

9.5.1 A Typical Performance Response Curve

Starting with an empty test environment, you should launch more and more copies

of the same transaction and watch a predictable pattern of round trip performance

emerge under increasingly higher workload conditions. Figure 9.1 illustrates what

the plot will look like if you keep adding more transactions.

50

40

30

"Knee" of

the curve

20

10

0

1

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

Number of round trip transactions

Figure 9.1

Round trip performance for catalog browse transactions

The

x

-axis is the number of transactions active at the same time. The

y

-axis

is the slowest response time measured for any of the active transactions. Using

either the average response time or the fastest response time for comparison with

the performance requirement will, in effect, mask the worst response times. A

reasonably well-designed transaction process will exhibit linear performance up

to a point, in this case 350 transactions. More than 350 transactions exhibit an

exponential response time. The point at which the trend changes from linear to ex-

ponential is traditionally called the “knee” of the curve. This curve infl ection rep-

resents some kind of bottleneck arising in the transaction process path. The plot

does not tell you the nature of the bottleneck, just the circumstances. Currently,

the only way to discover the location of the knee is to execute the workload and

plot the results.

Yo u r fi rst impression of using the performance curve might be that you

must push your workload till you encounter the knee of the curve, but that may

not be necessary. Consider the plot in Figure 9.2 and our business performance

requirement of 10 seconds maximum per catalog browse for a peak workload of

250 active transactions.

Box A represents the peak workload round trip response time of 250 active

transactions. At 250 transactions, the worst transaction response time was about

Search WWH ::

Custom Search