Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

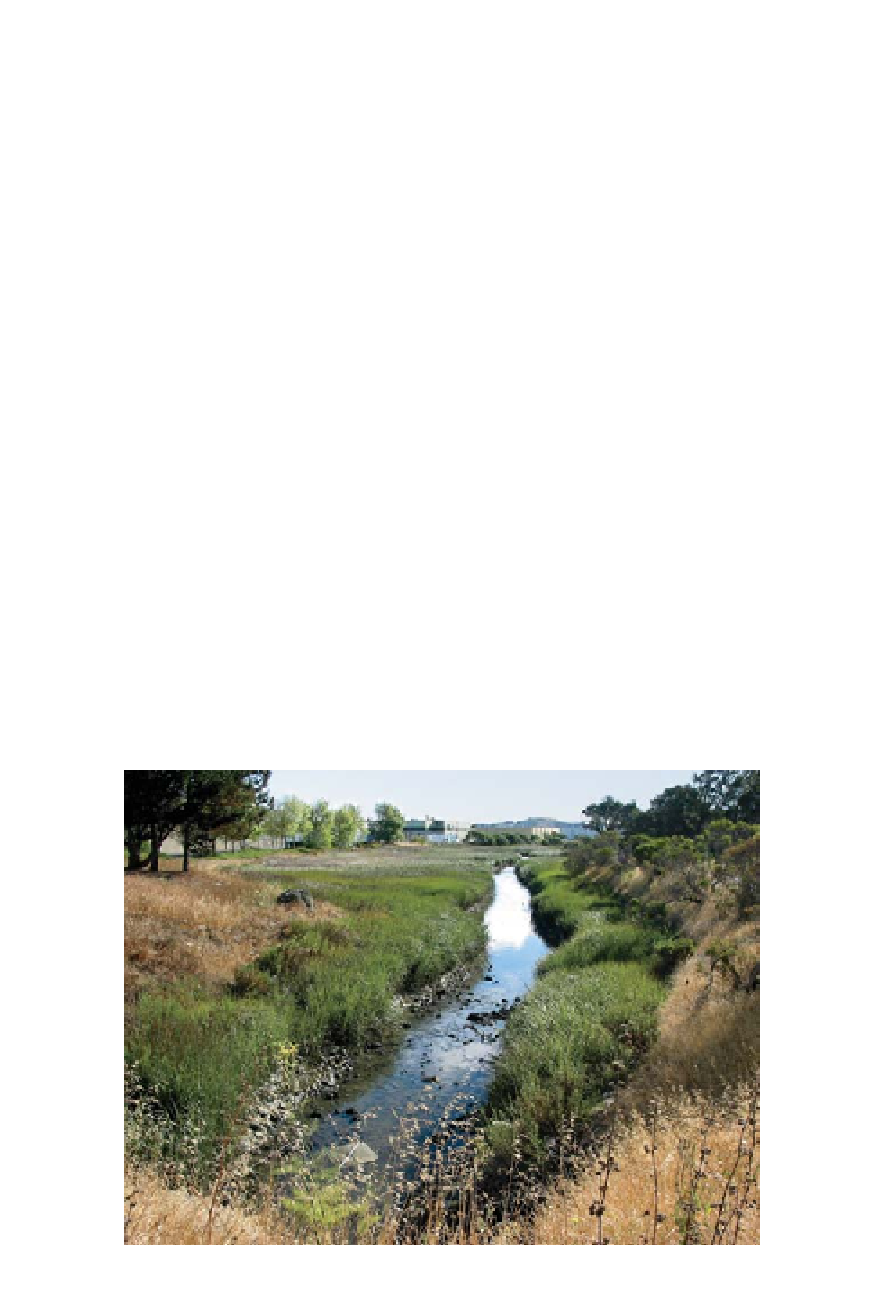

Dozens of creeks tumble from the steep slopes of the Coast Ranges onto

the flatlands before merging with the bay. The water that flows between

their banks is a highway that connects the ecology of the uplands to the

tidal estuary. From the leaves and sediments that drift from hilltops and

valleys; to the animals that travel between the ocean, marshes, and land; to

the fresh water itself that helps shape the aquatic habitats of the estuary,

creeks are an integral part of the estuary's anatomy.

In the Bay Area, creeks typically begin within creases in the steep

slopes of foothills and coastal mountain ranges. These headwater zones

collect water from natural springs or ephemeral runoff from storms. Far-

ther downhill, beneath the shady limbs of tanoak and bay trees, creeks

gather seasonal trickles, then coalesce into true streams punctuated with

still pools, gravel riffles, and sandbars. As the land flattens, streams may

peter out into alluvial fans or pool into freshwater marshes filled with

sedges and touched by the brackish fingers of the tide. “The ecosystem

doesn't draw a sharp line between creek, baylands, and bay. There's a con-

tinuum where these blend into each other,” says Phil Stevens, director of

the Urban Creeks Council. Every individual watershed recapitulates the

design of the larger estuary, with the tidal marsh at the foot of each creek

acting as its own miniature delta, and each creek mouth serving as a mix-

ing area for salt and fresh water.

Colma Creek near San Francisco's airport. (Jude Stalker)