Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

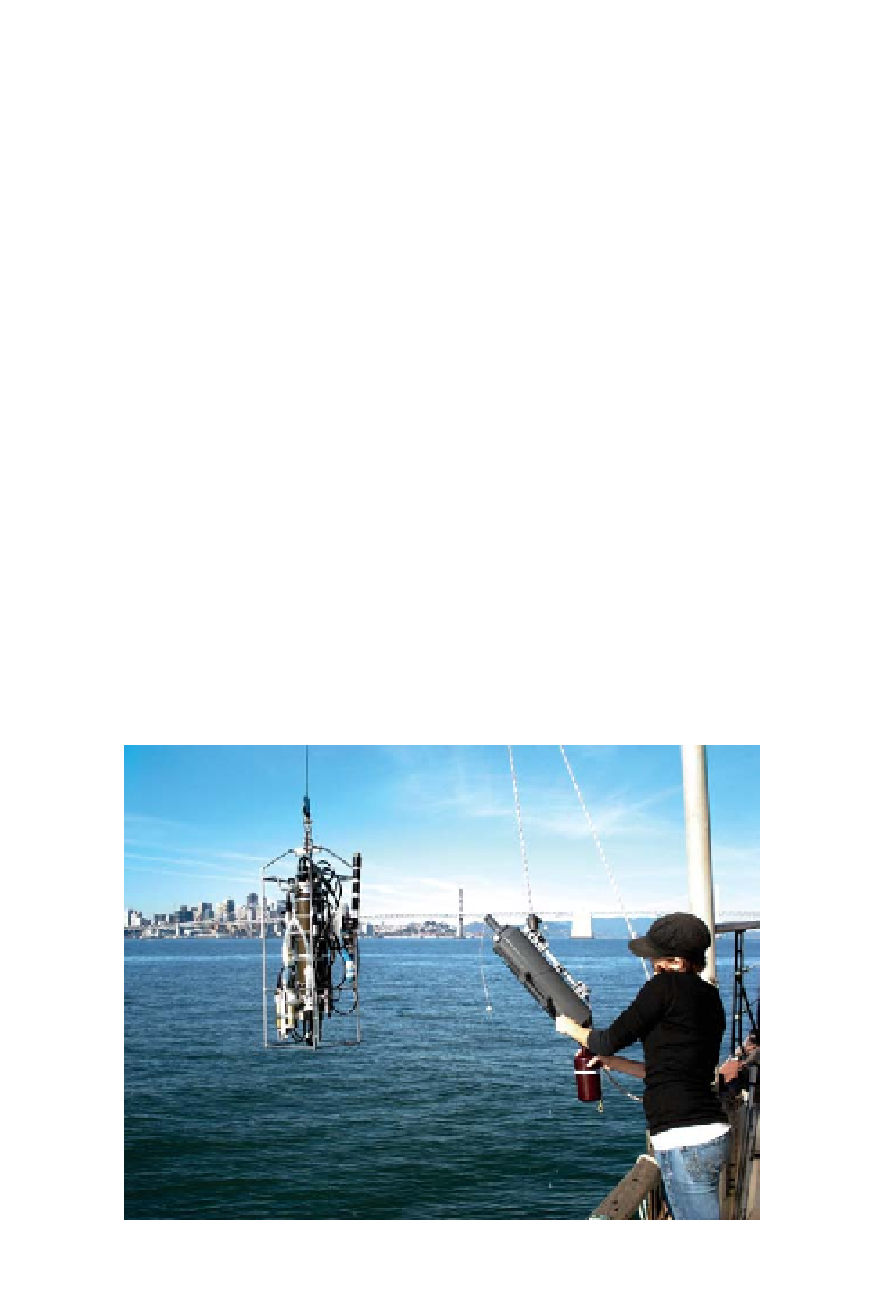

gauge, or CTD, measures physical conditions in the bay and feeds the information

back into the

Polaris

's lab computers. The instrument can take 25 samples per

meter, per second.

As the instrument descends to just short of the bottom and then rises back up

again, the crew works the keyboards and watches the incoming measurements

pop up on two screens. On one screen, blue, red, green, and black lines snake

their way down a graph as the instrument sends back a vertical profile of every-

thing going on in the water column. On another screen, numbers flash in white

boxes indicating GPS position, time, depth, salinity, temperature, turbidity, dis-

solved oxygen, and wind direction. When the instrument comes up dripping, the

crew leader presses the intercom and tells the captain, “Good to go.”

We repeat the same drill at a number of stations as the

Polaris

works its way

out of the southern backwaters and nears the Bay Bridge. Our top speed between

stations is about 10 knots. Our captain listens to the maritime traffic chatter on

the radio and watches a bunch of yellow dots (ships) on an on-screen nautical

chart move in and out of port. A click of a keyboard reveals the names of all other

Class A vessels over 65 feet long operating or parked in the bay at this precise

moment. This is no virtual harbor traffic game.

Past the Bay Bridge, the

Polaris

follows long trains of small white caps headed

east. I step out on deck and hold onto my hat to watch the crew undertake a spe-

cial set of experiments with a charcoal-grey PVC canister called the Niskin bottle—

a canister with a spring-loaded stopper on either end designed to “grab” water

USGS scientist deploying a Niskin bottle (right) and CTD (left), instruments used to

measure physical conditions in the bay. (Ariel Rubissow Okamoto)