Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

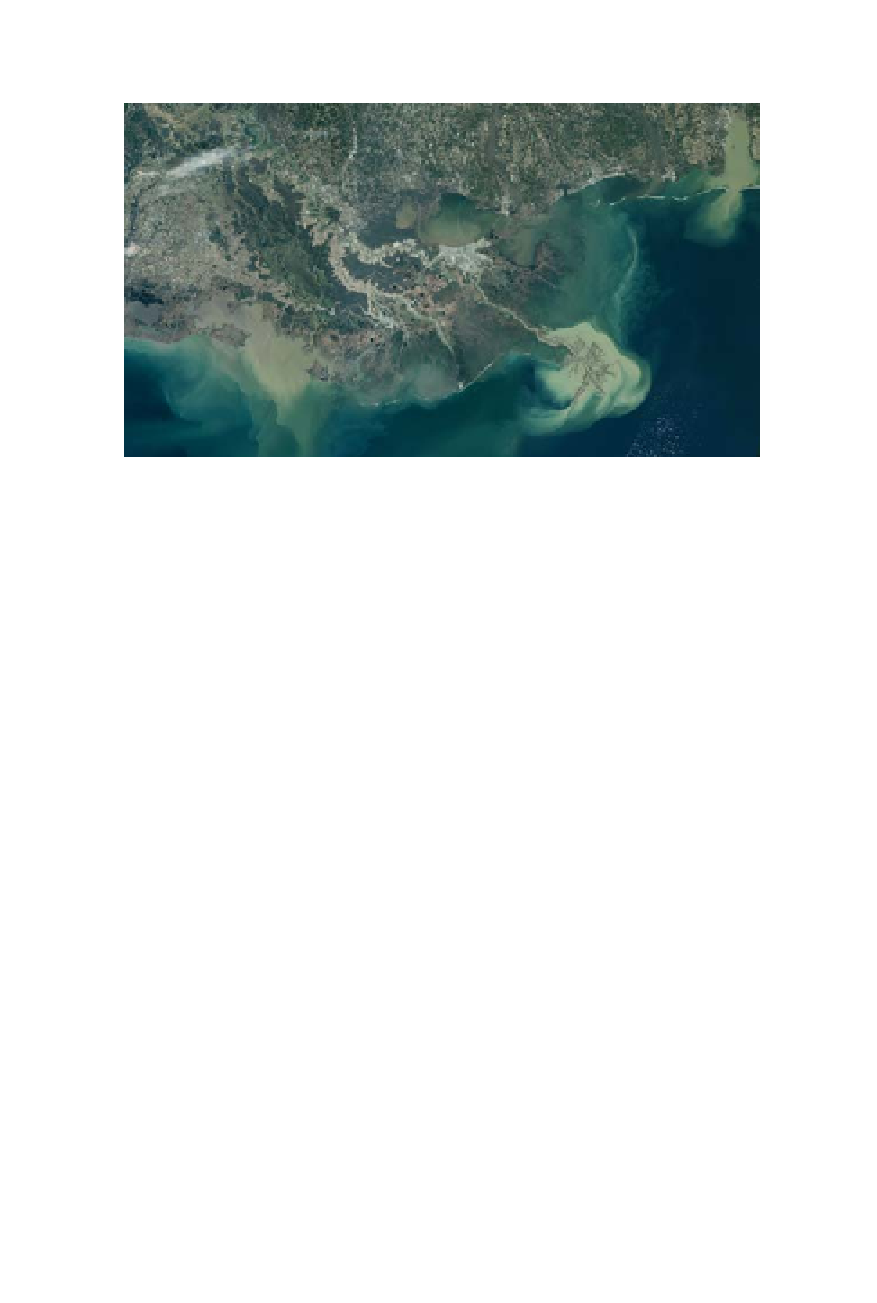

nation's interior out into the sea. Only in San Francisco Bay did the power of flow-

ing river water and rising seas cut gaps in the hard rock of coastal ridges. (NASA

Goddard Space Flight Center)

the water gets deeper and faster; at each opening it shallows, slows, and

warms.

“It's a really weird estuary,” says Herbold. “These two rivers cut down

and form a big delta, and then they come back together into one little

bottleneck out into the bay. Shapewise from the air, it looks like it should

be flowing the other way.”

The forces that created the estuary's unusual geography thrust moun-

tains up from the seafloor and warmed or cooled the climate enough to

cause a change in sea level. The estuary has only been around for about

5,000 years in its current shape. But geologists trace the building blocks

back much further. Rock and soil profiles under the bay and in the coastal

cliffs reveal at least three periods during which the sea level rose and fell

across the landscape in step with glacial changes over the past million

years. The most recent rise occurred about 15,000 to 18,000 years ago. At

that time, Pacific waves didn't crash as far east as they do today. The shore

extended out to the rocks of the Farallon Islands, and river waters empty-

ing out of the valley and through the Carquinez and Golden Gate straits

still had 20 miles to go west of today's gate before meeting the sea.

Geologist Doris Sloan paints a picture of this time in

Geology of the San

Francisco Bay Region

: “On a sunny weekend you could have hiked out

across the broad, gently sloping continental shelf for a picnic on the Faral-

lon Ridge overlooking the Pacific Ocean to the west. Or you could have

stood on the headlands above the Golden Gate and watched the mighty

flow of the river as it poured through the valley, tumbling over great cas-