Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

we'd done before, and for what mix of new tidal wetlands and existing

managed ponds we needed,” says Amy Hutzel, manager of the San Fran-

cisco Bay Area Conservancy, a state agency that has since played a key role

in securing properties for restoration. This mix had been a sticking point

for many earlier projects.

The region then launched a new organization to help coordinate im-

plementation of the goals. The San Francisco Bay Joint Venture would

consist of a partnership of on-the-ground wetland, wildlife, and shoreline

managers from both government and nonprofit organizations. Its work

also embraces national U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service efforts to sustain the

wetlands, coasts, and waterways that ducks and geese depend on as they

migrate through the United States and Canada.

But the real impetus behind bay wetland restoration sprang from Cali-

fornians' growing support for clean water. “People liked projects that

made the water environment better, that gave them clean, safe, reliable

water—whether they were drinking it from the tap or touching it on the

bay shoreline,” says Steve Ritchie, who once oversaw regional water quality

and supply programs and later ran major restoration programs both up-

and downstream. “Everyone thought restoration was a worthwhile invest-

ment.” Voters overwhelmingly approved money for delta restoration in

1996 with Proposition 204, and for bay restoration in 2000 with Proposi-

tions 12, 13, 40, and 84. “It was a sea change in our approach to clean water

and environmental quality, the beginning of the serious age of restora-

tion,” says Ritchie.

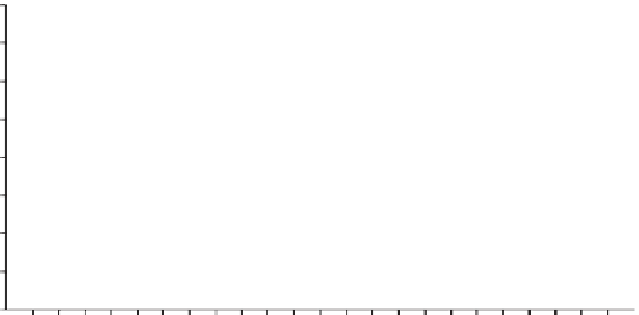

Since then, every region of the bayshore has benefited from new sci-

ence, new partnerships, and new funding for restoration. According to the

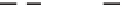

4,000

3,500

3,000

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

0

prior to

1986

1990

1995

2000

2005

2008

Figure 16. Acres of salt pond and other habitat opened to tidal action since the

1980s. (S.F. Estuary Institute)