Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

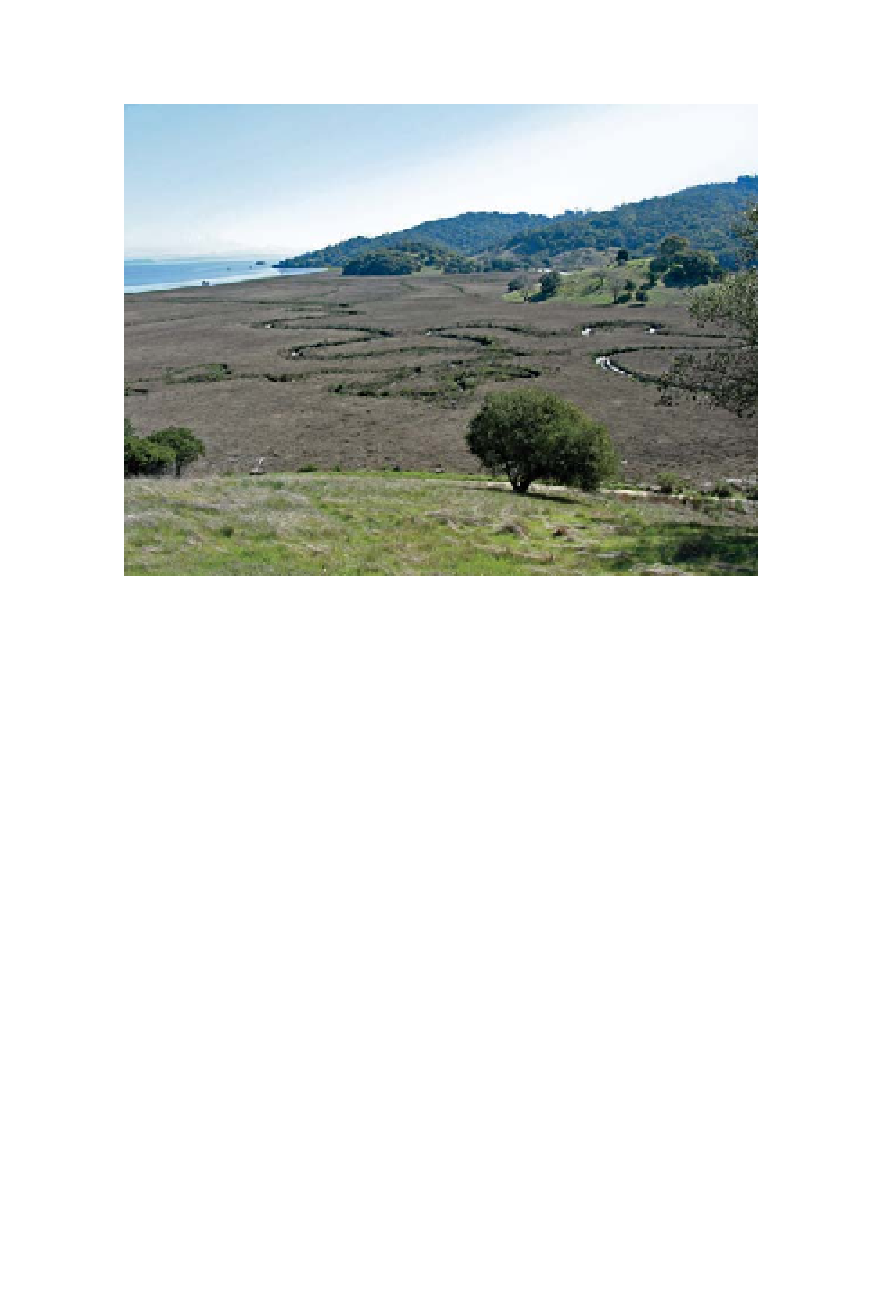

Scientists turn to old marshes as reference points for wetland restoration. Marin's

China Camp Marsh is one of the few remaining ancient bay marshes with a com-

pletely intact watershed; its fresh to brackish saline gradient supports diverse na-

tive plant species. (Jude Stalker)

grass marshes of Georgia described by scientist Eugene Odum, so every-

one looked east to re-create marshes out west.

In the 1970s, local action around wetlands focused on dredged mate-

rial disposal sites, with engineers seeking ways to speed the transforma-

tion of these sites from glistening fields of mud to green marsh. The U.S.

Army Corps experimented with methods of promoting cordgrass growth

to stabilize banks and vegetate mudflats along Alameda Creek in the East

Bay. They considered several options: sowing seeds, planting sprigs, or

transplanting whole clumps. According to Phyllis Faber in a 2000

Coast

& Ocean

magazine article, the Corps's experts noted the poor seed set of

the local native cordgrass and opted instead for a hardier, more produc-

tive cordgrass stock from the Atlantic coast. Though they meant well in

choosing the most prolific species, they had little idea that they were in-

troducing a destructive alien that would cost millions to get rid of de-

cades later.

Most of the early restoration projects in the 1970s and 1980s involved

no more than an acre or two, and most were done as mitigation for the

paving over of wetlands for shoreline development. New, postage stamp-

sized wetlands sprang up here and there as a result. “Developers wanted to

claim that they were immediately creating the same value in wetlands that