Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

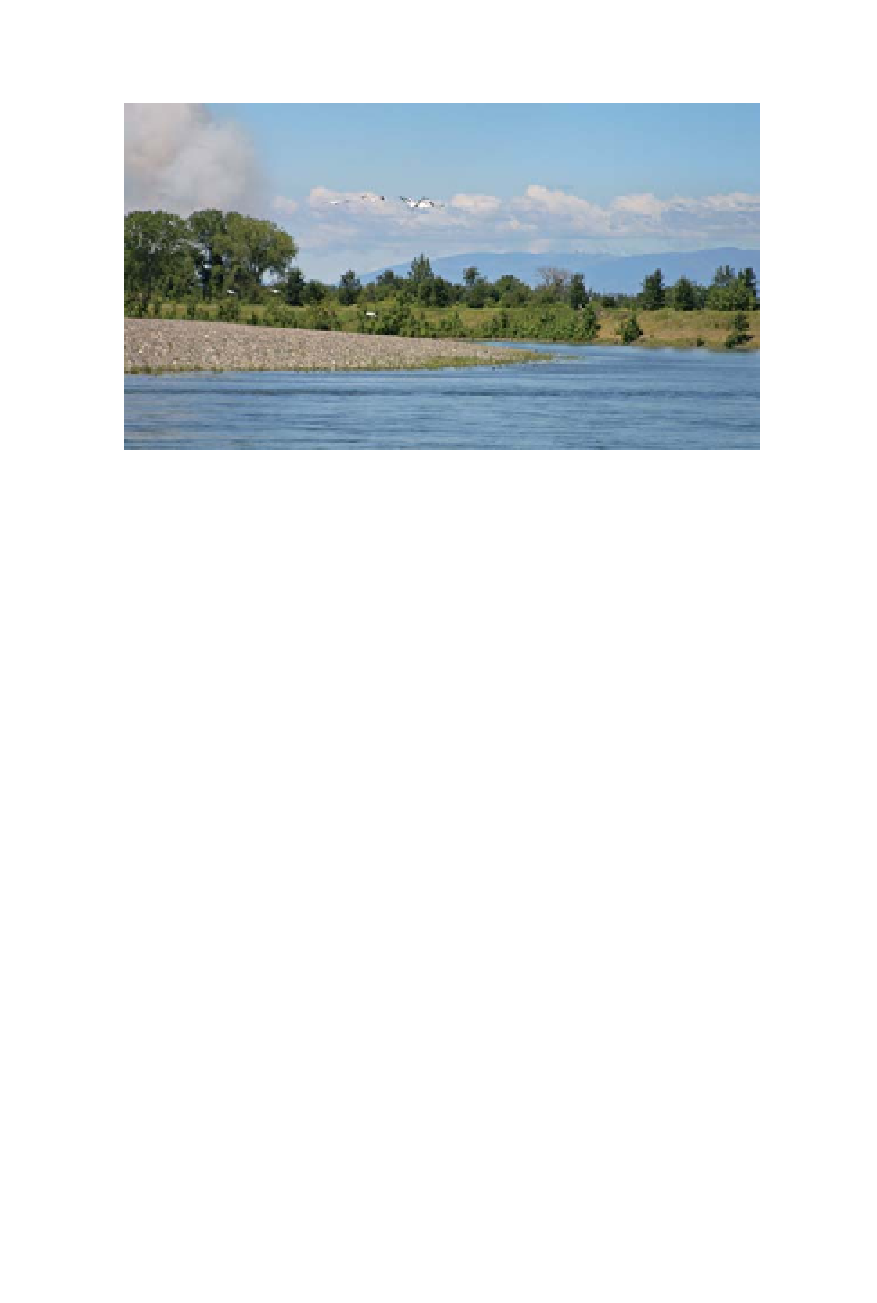

Rivers make new land such as this point bar on the Sacramento River. As the chan-

nel moves away from one bank, gravel collects on the other, allowing cottonwoods

and other plants to take root. (Eric Larsen)

been “seasoned”—the small rocks having rolled around, interacted with

the water, released minerals, and accumulated algae.

With so much concrete lining their shores, rivers and creeks also need

new spaces for vegetation to grow, trees to rise, and logs to fall. They need

setbacks to invite water onto old floodplains, or bulldozing to re-create a

long-lost meander or bend.

“People have historically thought that a migrating, eroding channel

meant something was wrong, that a raw riverbank was a bad bank,” says

UC Davis's Eric Larsen, a fluvial geomorphologist who is one of the “go-

to” guys for Sacramento River restoration. In reality, rivers create new land

by eroding and redepositing sediments. “The river is not alive unless it's

migrating. All its ecological processes are built on the basis of the river

moving across the floodplain.”

Riparian specialists concocting restoration recipes are now thinking

big. They seek to re-create river processes across entire landscapes. They

are looking beyond the need for a new riffle here or a better fish screen

there, to how best to sustain 10 mile to 100 mile reaches of river. It is only

on such broad scales that riparian processes—in which water, sediments,

seeds, and fish interact—come into play. And it is only on these scales that

the pitfalls of gardening-style restoration, where benefits are highly local-

ized and often short-lived, can be avoided.

Beyond adding good ingredients in the right quantities, any recipe

must also keep bad ingredients out of the mix. Poor water quality from

agricultural and wastewater discharges, harmful invasive species, and high

water temperatures can all too easily negate the value of restoration, or

impede its intended purpose.