Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

The Port of Oakland invested in hulking dockside and rail-mounted

cranes in the 1960s. It also dredged deeper berths, hired more crane op-

erators and longshoremen, and embraced its future as one of the top five

intermodal ports in the nation, moving shipping containers among boats,

trains, and trucks. The Ports of San Francisco, Richmond, and Redwood

City also continued to expand and modernize their maritime facilities, as

did the navy, on 21 bases around the bay.

Traffic on the bay grew busier. Tugs and dredgers worked to keep the

ports and marinas from silting up. Bar pilots guided giant oil tankers, con-

tainer vessels, and cruise ships in through the narrows, fogs, and shoals of

the Golden Gate, and longshoremen loaded and unloaded containers and

cargoes. Coast Guard crews rescued vessels, surfers, and swimmers in dis-

tress, and responded to oil spills and wayward whales. Local marinas and

yacht clubs grew to support a spurt in recreational boating and sailing.

Today, the bay floats vessels of every stripe. More than 1,000 commer-

cial fishing boats consider the bay home port. Speedboats, sailboats, kay-

aks, and windsurfers also ply these waters for pleasure, steered and pad-

dled by some 225,000 recreational boaters. Four thousand commercial

ships move in and out of the bay's harbors annually, and cruise ships often

brighten San Francisco's piers with their white flanks and twinkling lights.

The bay and delta's reliance on water for commerce, recreation, and

transportation endures to this day. But in the 1960s, associated maritime

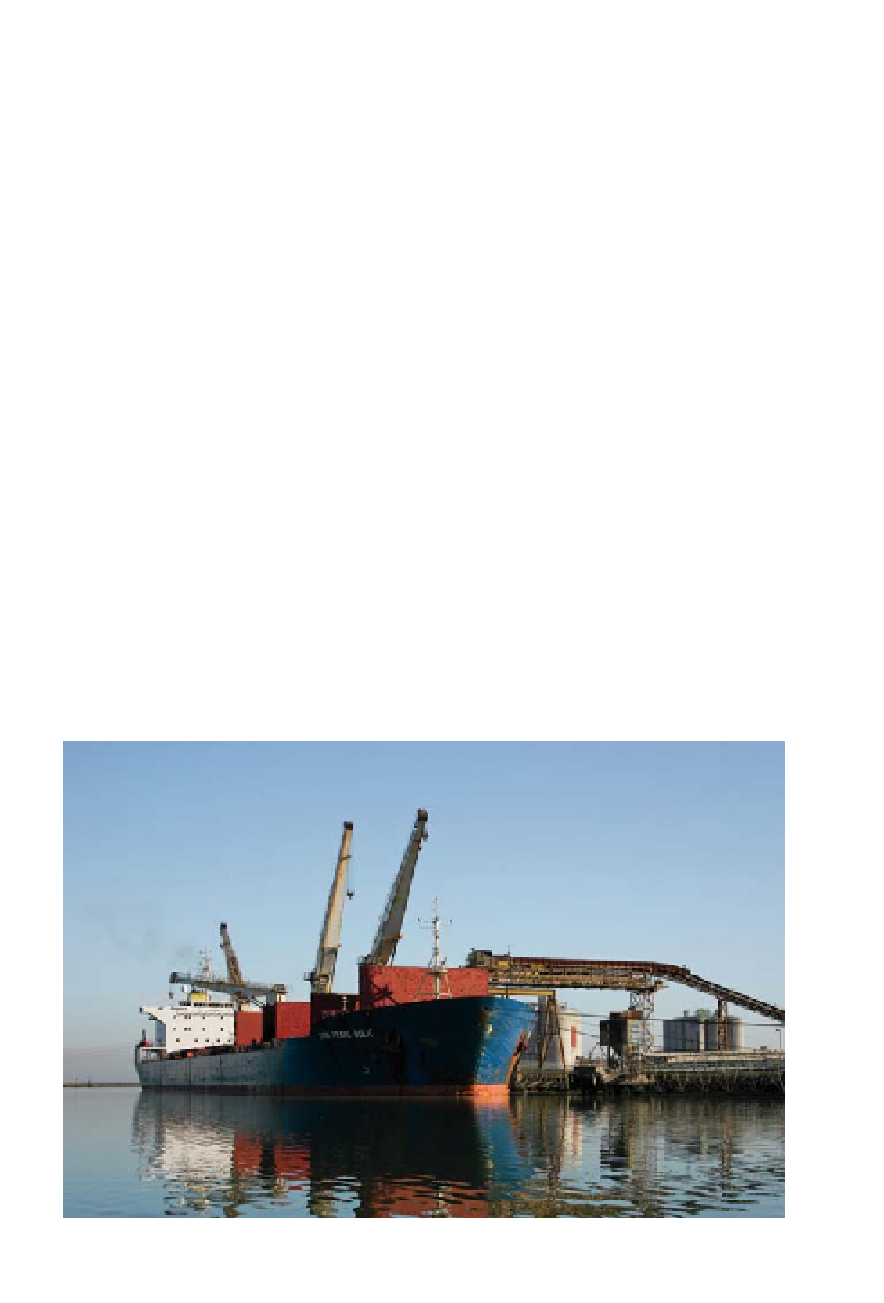

A ship equipped to load diverse cargoes—”breakbulk”—in its holds. The port of

San Francisco hosts the bay's primary breakbulk facilities. (Francis Parchaso)