Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

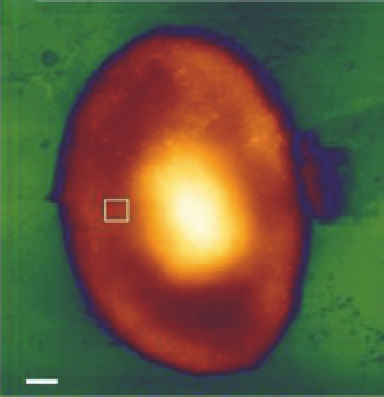

(A)

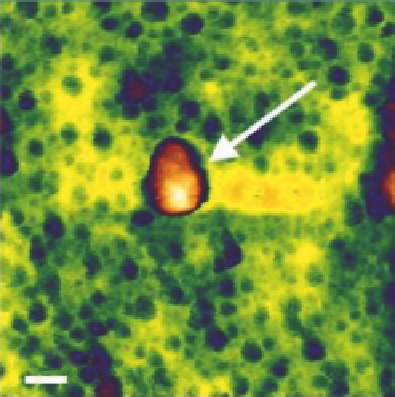

(B)

100 nm

1

µ

m

FIGURE 21.14

Influenza virus particles associated with the surface of an erythrocyte. The overview image (A) and

higher-magnification image (B) of the red blood cell surface show influenza virus particles (white

arrow)

[20]

.

are specifically captured from a sample solution on the surface of our sensor

[21].

This is illustrated

in

Figure 21.15

.

21.8

NANODENTISTRY

There are significant advances in dentistry that illuminated the road for the shift from “macro” to

“nano” in dental sciences. It is evident that increases in the versatility of scientific knowledge and

the ability to control physical processes at a finer resolution naturally lead to more information and,

henceforth, to more questions. The broader our knowledge, the more amazement arises in face of nat-

ural wonders

[22,23]

. The same could certainly be said for the field of dentistry. The historic progress

in this area naturally goes hand in hand with many new questions and challenges that provide oppor-

tunities for improvement. The progress, admittedly, has been slower than might be considered desir-

able for those who would wish to put a cutting-edge technology to clinical use. For example, early

descriptions of the extraction of teeth with the use of forceps by Hippocrates and Aristotle date back

to 500-300 BC, a technique that has remained essentially unchanged till date. Likewise, restorations

with amalgam and gold date back to years 700 and 1746, respectively, and are still a part of our clini-

cal setting without much change.

21.8.1

The Impact of Nanotechnology

It is, on the other hand, valid to point out that nanotechnology slowly had made its way from the

lab bench to any other technological or medical field. This is hampered not only by slow progress